This was written during the 2023 WGA and SAG/AFTRA strikes. The work covered here would not exist without the labor of the writers and actors currently striking for improved working conditions and fair pay.

::

I. TONSILS & ROY ROGERS

When I was five, my sister had her tonsils out. Mom stayed overnight at the hospital with her, which left Dad to figure out what we were going to do with our evening together.

We found ourselves at dinner at the Roy Rogers on Reisterstown Road - a treat for me, an easy solve for Dad (no shade - as a father to a ten year old myself, I know that job one is filling the hours) - when Dad glanced across the street to the twin cinema at the Plaza with a “… Huh,” and asked if, after dinner, I might want to go over to the mall to see The Empire Strikes Back, in its 1982 rerelease.

(Yep, drop what you’re doing, Internet, a white guy in his 40s is gonna talk at you about Star Wars)

Back at Roy Rogers some 41 years ago (fuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuck me), I froze, mid-fixins-bar-heavy-bite, for two reasons:

In my family, movie nights were plentiful, but usually rigorously slotted in around my parents’ work schedules, my sister’s & my sleep schedule, etc., so the very idea of just … deciding to go to a movie like that was like eight nights of Hanukkah compressed into one suggestion (to this day, impromptu movie nights are one of my top five favorite things), and

I was five years old and Empire Strikes Back was my most favorite movie of all time (since then, it’s dropped a whole one, maybe two slots, behind other movies with passages to be covered in future posts), so

I’m sure I didn’t respond with “Fuck yeah!” bc being a kindergartener, it wasn’t in my vernacular yet, but in some primitive form, the sentiment was there.

We finished up our, I dunno, horsey burgers?, and crossed to the mall. This being decades before reserved seating, you could just go into the end of the previous screening and wait for your showtime to begin.

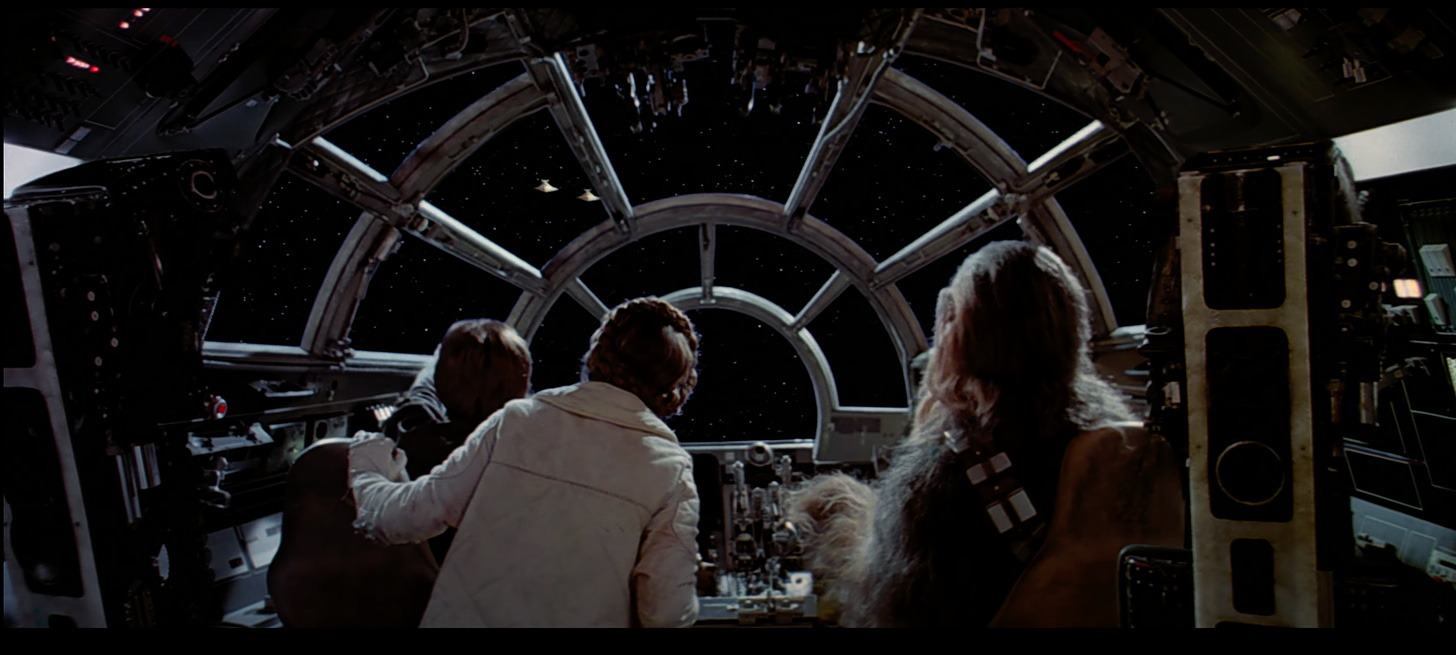

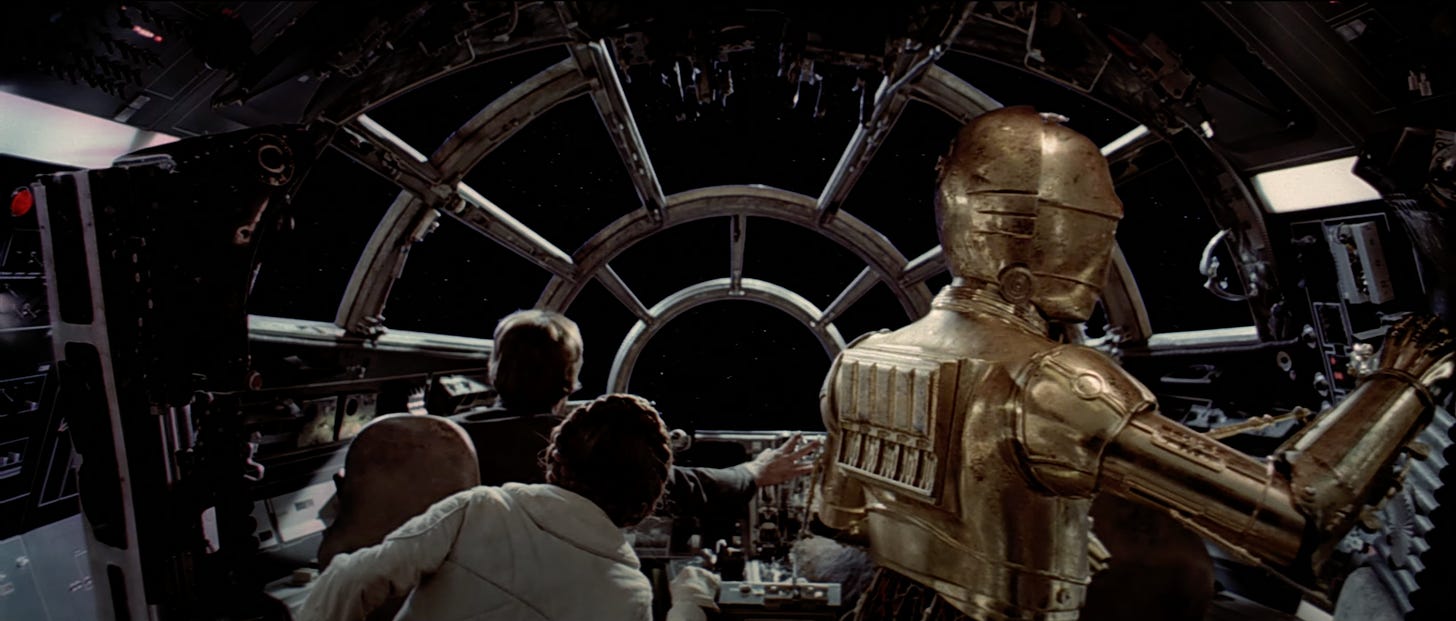

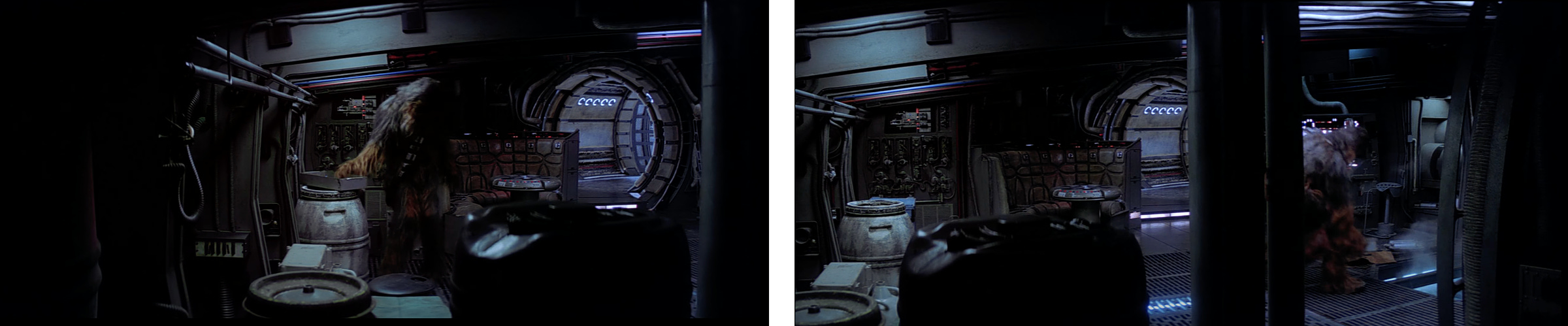

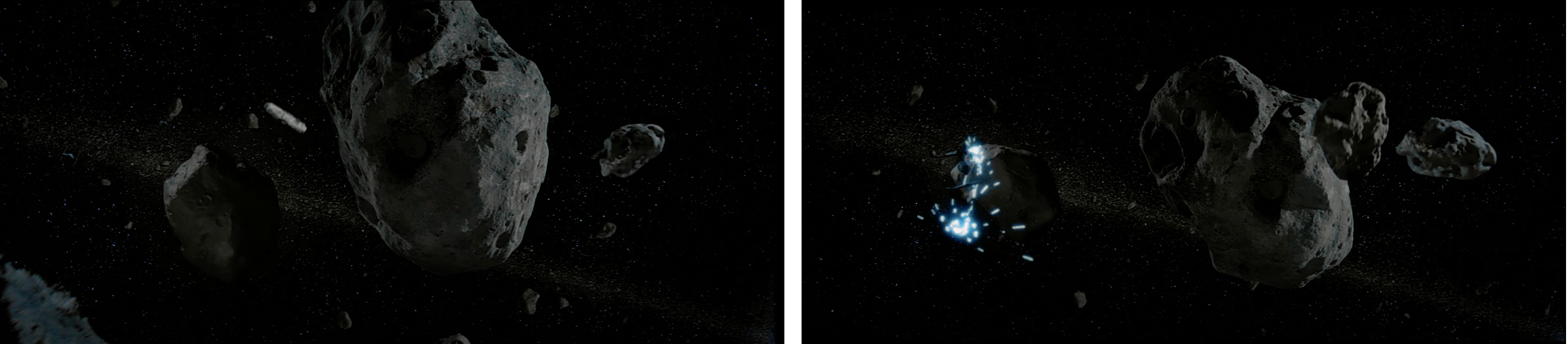

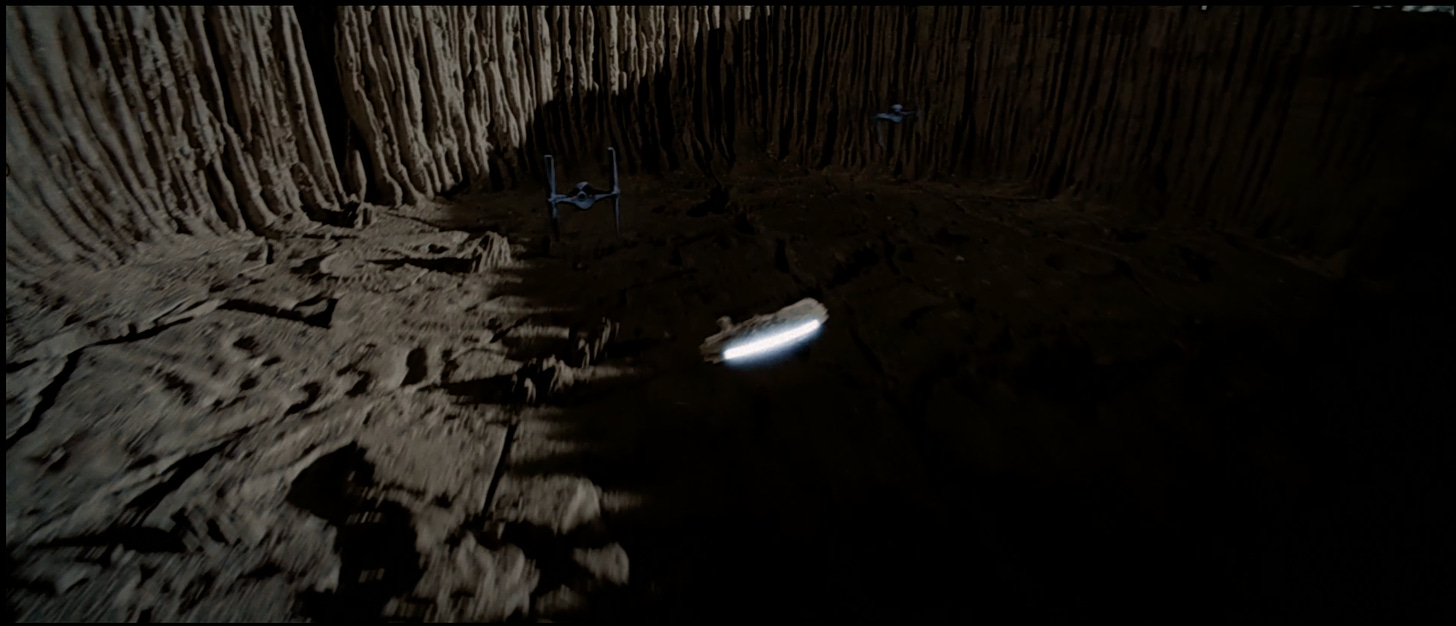

BTW, this is the exact moment we walked in on, and to this day, because of that day, it’s my favorite shot in all of Star Wars:

In more ways than one, that screening proved to be something of a radioactive spider for me, when, before our showing, they ran the first teaser trailer for Return (then still Revenge) of the Jedi, which I had no way of knowing till years later, put me on the path toward producing promos & trailers, which I do to this day. (I “returned the favor” a few years ago in a Star Wars campaign I was working on with an homage that never made it to air)

I’m pleased to say that, for as great a high as that whole evening was that 40+ years later I’m still musing on it, I’ve hit similar highs with Star Warses since then (up to and including taking my own five year old to Last Jedi).

But for all the childlike glee that Empire inspires (and, indeed, was designed to inspire), I never got half so much enjoyment from it until its blu-ray release, which was the first time I can remember approaching the material as an adult, and finding that there’s just as much - if not more - to enjoy about it. This is probably why Empire tends to stand out of the pack not just for me, but in critical consensus - it’s a grown-up tragedy, thoughtfully executed by adults, wrapped comfortably in a kid’s Halloween costume.

Watching it with adult eyes, not to mention in hi-def, I was able to better appreciate DP Peter Suschitzky’s and production designer Norman Reynolds’s use of color and framing - both a vivid upgrade from the stark blacks, whites, and browns of A New Hope - and Irvin Kershner’s playful, layered staging.

Around the same time, I read JW Rinzler’s indispensible The Making of Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (a friend of mine once described Rinzler’s trilogy as the first thing he’d grab if his house were on fire; his kids, second), which for the first time in my life made it clear to me that every piece of art is built one decision at a time, never more than a choice or two away from failure.

This visual and philosophical reappraisal brought me back to my favorite sequence - the jewel in the crown of the jewel in the crown:

The Asteroid Field.

FAIR WARNING, since we’re all new here: I will be discussing this scene (and other key beats related to this scene) in great detail, offering interpretations, observations, and inferences along the way. If you haven’t seen The Empire Strikes Back, spoilers ahead.

(BTW, if this essay is your first exposure to Empire Strikes Back, please contact me bc I am deeply curious about your whole deal)

At the time of Empire’s release, it wasn’t hard to see this sequence as a standout (considering the grand total of Star Wars material was four hours and change, or if you count the Holiday Special, eighteen hours). Even now, nearly half a century later, you could take the total tonnage of the days’, maybe weeks’ worth of Star Wars (oh that word) content, and leave me the Asteroid Field and I’d be fine. (Ok, maybe a few other highlights, too, like I’m Navin Johnson cherry-picking a paddle-ball, ashtray and chair on the way out the door)

There’s an extent to which the Asteroid Field in particular, and Empire at large, is George Lucas’s self-clapback at the technological and financial limitations that, from his POV, compromised A New Hope (even while it pried the world’s third eye open; while it’s said that nobody hates Star Wars more than Star Wars fans, I’d argue Lucas has the edge).

Specifically, the Asteroid Field feels like a mulligan of the first movie’s escaping-the-Death-Star dogfight, which keeps the VFX compositions tight, possibly owing to technical constraints. Nobody would call that sequence sedentary (thanks in large part to Marcia Lucas’s editing and John Williams’s score), but it’s not hard to imagine George Lucas squirming like George C. Scott in Hardcore, seeing only the imperfections in the execution, and roadblocks to his vision.

But then, with the success of Star Wars so overflowing the bank that they had to open new banks, Lucas and team got a shot at a do-over, this time with the throttle open and nothing but green lights. What they came back with was, to me, unmatched perfection.

II. You’re Not Actually Going Into An Asteroid Field

The start of the second act of a story can be a tough gear to shift. Fortunately for its creative team, propulsion is the name of the game in Empire, a movie that rarely if ever sits still. Here, the story shifts from the first act’s focus on the heroes’ interpersonal dynamics to a chase movie which, for one cohort of the separated protagonists, it remains nearly until all but the final moments.

Having escaped the brutal assault on the new rebel base - not to mention a run-in with the local fauna that’s left him near-death and seeing ghosts - Luke Skywalker surprises his droid companion R2-D2 with his intentions not to rejoin the squad, but to go off on a splinter mission to chase his destiny.

Like R2, and Luke himself, we’re not positive this is a great idea, and our sentiments are echoed by John Williams’s wavering, three-layer, minor-key woodwinds that manage not to sacrifice the intrepidity of the moment as Luke temporarily exits the story, while sounding a warning for what’s to come …

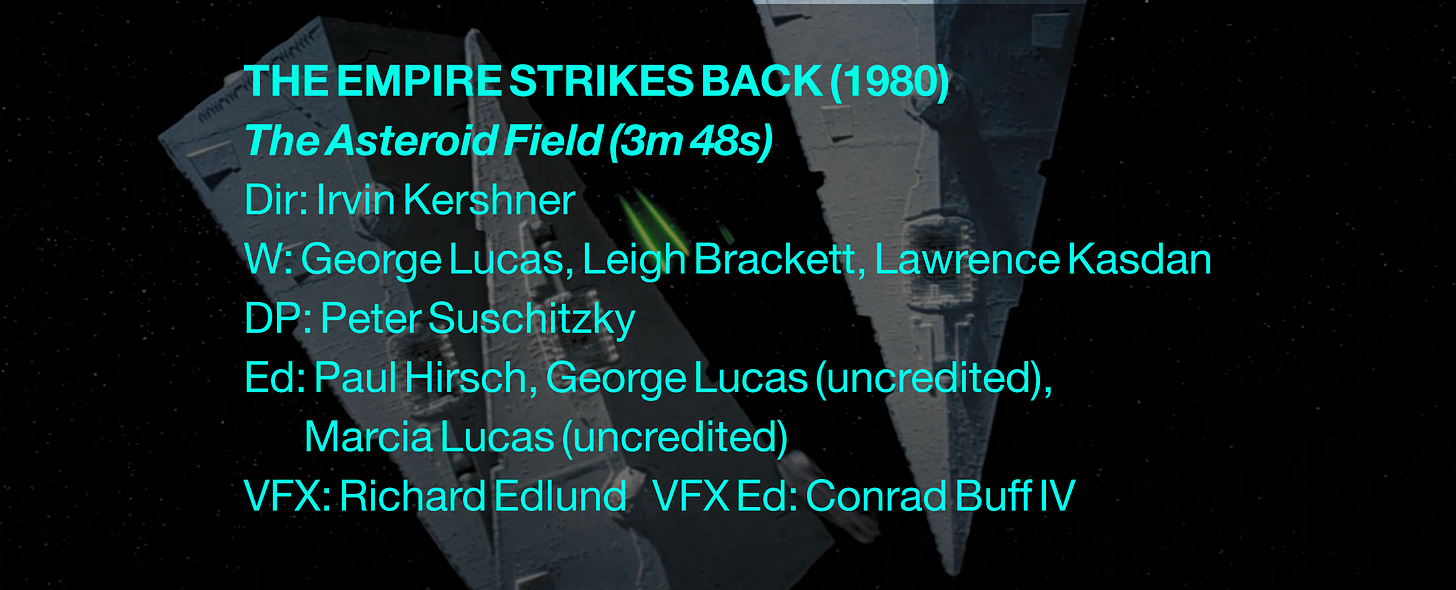

We’re told in no uncertain terms that the ground is shifting under us. Where Luke’s exit is a single, receding X-Wing against a vast starfield, we immediately wipe to the Empire’s pursuit of the Falcon in medias res, the Star Destroyer filling the frame, dwarfing the fleeing rust-bucket (shades of the opening shot of ANH, but if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it).

This contrast is invoked more directly in the reverse angle —

— as the approaching Star Destroyer visually swallows the fleeing Falcon. (This shot also more clearly establishes the four TIE Fighters that dog the Falcon through the sequence).

Two things to keep in mind about the opening salvo of these shots:

Each of these elements - four TIE fighters, the Falcon, the Star Destroyer - would have been shot separately and then composited, a Sisyphean but invisible miracle that recurs approximately every two and a half minutes throughout the trilogy.

Since the motif was only introduced in this movie some twenty minutes earlier, this is only the fourth or fifth time in their lives a first-time viewer would have heard the Imperial March. Wild to think about a moment when that was true.

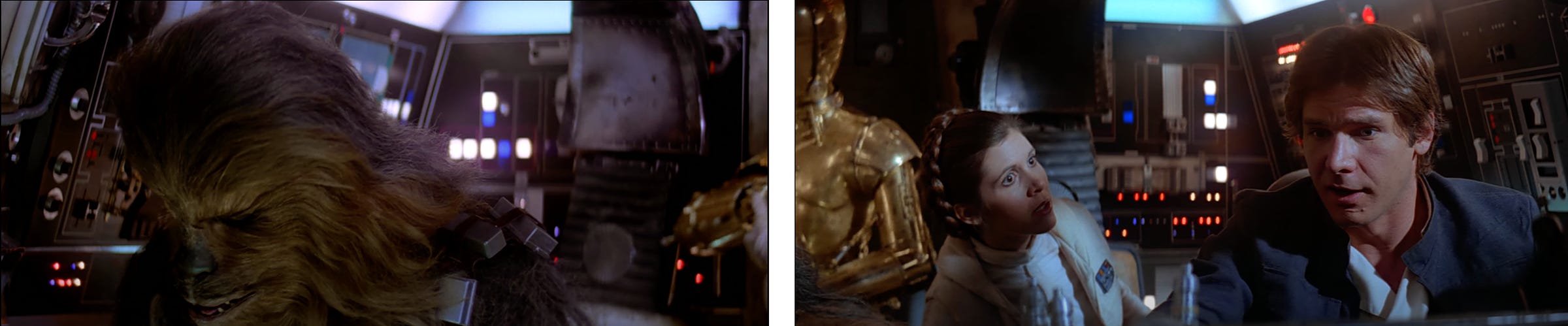

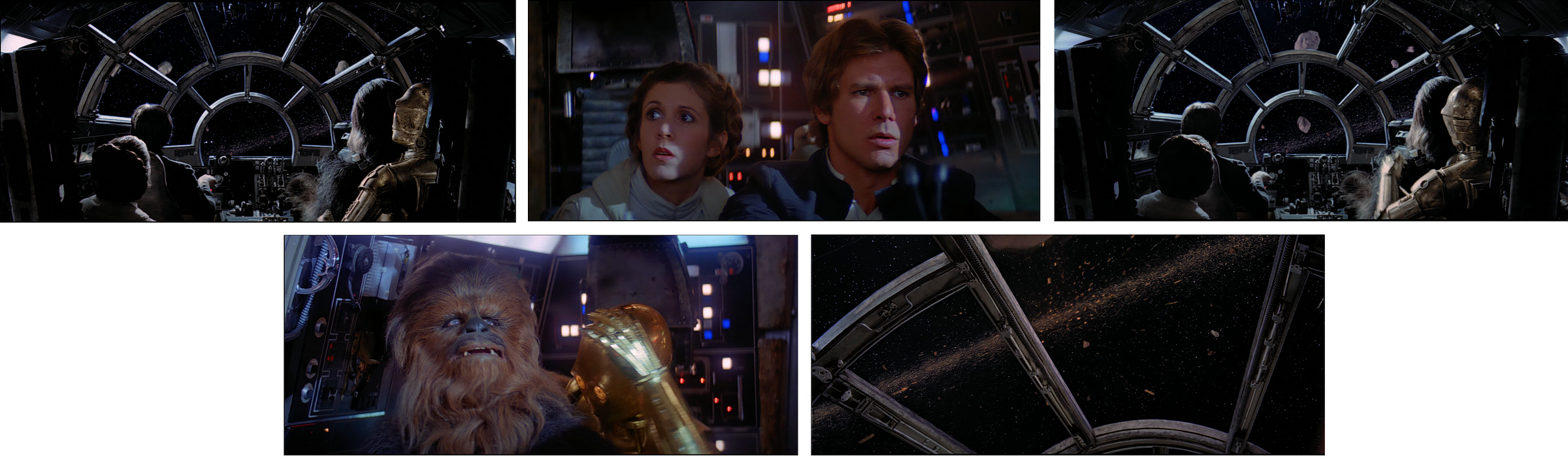

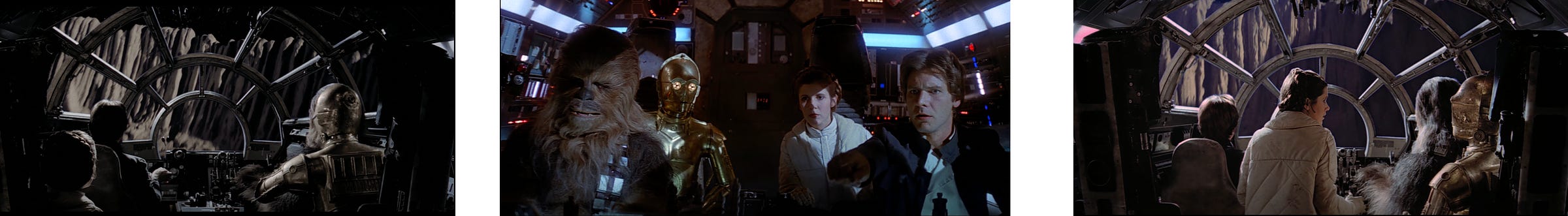

From here, we move inside the Falcon’s cockpit, where we begin to settle into the heroes’ dynamic that drives the rest of the act - it’s like a family road trip already in the advanced stages of are-we-there-yet, painted in Suschitzky’s chiaroscuro comic book palette; when a laser blast fleetingly lights up the cockpit, it’s not blinding white, but a lush gold. (Empire has, for my money, the best cinematography of the series, and it bums me out a little when each new one doesn’t try to recreate it, but your mileage may vary, of course.)

The deft framing of these shots establishes the characters’ evolving dynamic - Han and Chewie aren’t exactly on-the-outs, but the situation is changing. Here, Chewie is alone, stoic in his no-fuss co-piloting, while “Mom and Dad” are isolated and bickering in their shared frame.

The exterior and interior threads are reconnected in the “backseat” shot so familiar from ANH, that introduces the encroaching, intensifying threat from the front.

(Note: You don’t need me to tell you this is an iconic set-up, but my main gripe with The Force Awakens is that they missed the opportunity for a heartbreakingly powerful moment; had they staged Chewbacca’s grief over [SPOILER] Han’s death with Chewie alone in this framing, his loss and ours would have compounded each other. Call me, JJ.)

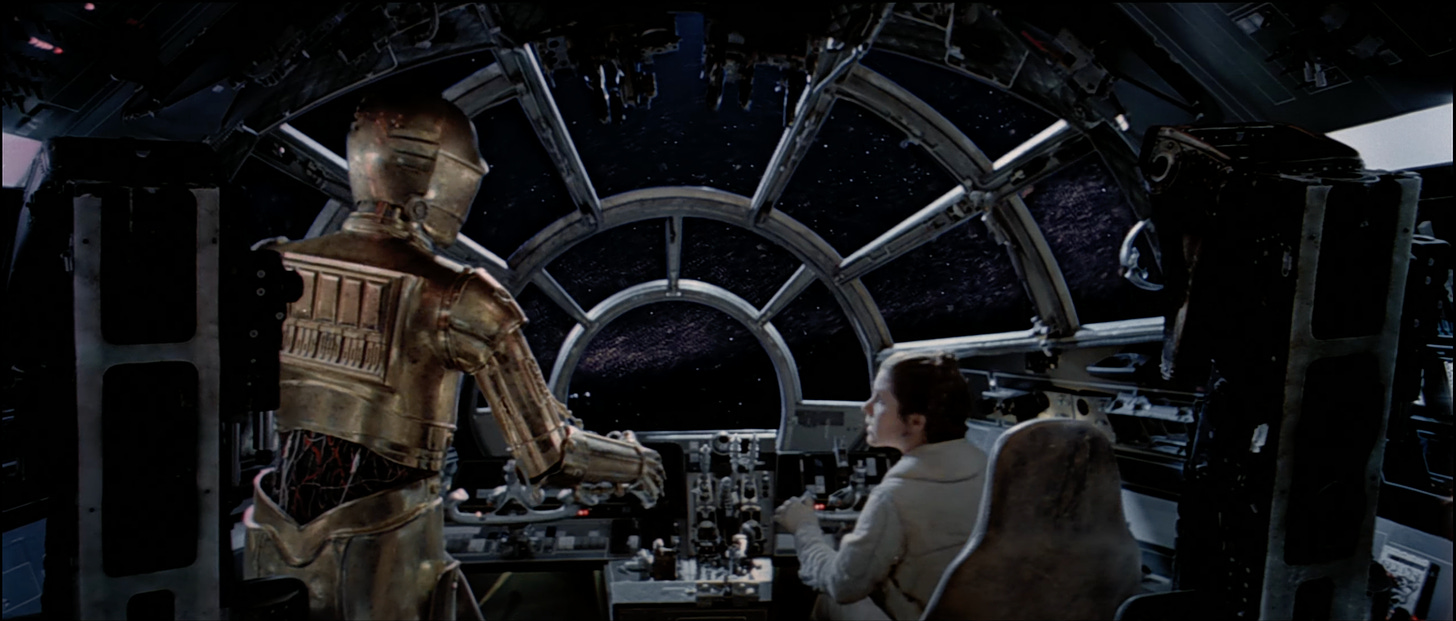

We seal in the family dynamic with the arrival of kid brother 3PO - a necessary and helpful bit of resetting the table, in case we hadn’t tracked who wound up where while escaping Hoth, ratcheting the already tense cockpit into stop-touching-me bumper cars, ending on a quick note of Han taking the situation in hand, showing determination for the first time in the sequence, and with good reason:

To the best of my recollection, this is one of the series’ first - if not the first - use of the z-axis, reminding us that for all its car-chase linearity, this scene is set in SPACE. There’s no up or down, so why not use it all? The Falcon’s barrel roll dive - intrinsically joyous, contextually panicked - feels like Richard Edlund’s team showing off, and why the hell shouldn’t they?

Of all my crystal clear recollections of this movie and my experiences with it, I wish I could remember what seeing this for the first time felt like. It had to have been wild.

For the first and only time in the sequence, we put a face to the heroes’ pursuers, in this case a comic beat clowning on the Empire’s clumsy Goliaths, and letting us know that the agile Davids aboard the Falcon have the upper hand for the moment.

(It occurred to me on my most recent rewatch that we don’t get the TIE fighter interior pilot shots typical to the visual vocabulary of similar Star Wars beats, which again keeps the personality squarely planted aboard the Falcon, its pursuers quite literally anonymous.)

Critically, too, we’re reminded that this is a regular-degular Star Destroyer, and not Darth Vader’s flagship, level-setting the stakes to reassure us that while it’s bad for our heroes, it could certainly be worse.

More z-axis fun follows as the undersides of the Star Destroyers form a snaggletoothed jaw from which our heroes have escaped (for now - everything in this movie is “for now,” more on that in a minute), foreshadowing the space slug beat a few scenes downstream, and adding a style of visual we haven’t yet seen in the series.

Here, too, the action reorients, with the Falcon repositioning to move from camera-right to camera-left, the direction of the action for the remainder of the sequence (tentatively established by Luke’s exit at the top of the sequence).

The Falcon rights itself, the more nimble TIE Fighters still on its back. Like I said, every victory in this movie is just “for now.”

The larger obstacle evaded, we get a repeat of the same sequence of shots from our first time in the Falcon’s cockpit, ready for the jump to lightspeed —

— and the Backseat Shot again —

— where we get into Empire’s steady comedic runner of the broken hyperdrive. This beat works by playing on our expectations from ANH - effectively parodying the first movie’s thrills - when the shot where the ship should jump to lightspeed yields nothing.

We should talk for a moment about the precision of Harrison Ford’s facial expressions in this scene - the drawbridge lift and drop of his brow, the rise and fall of his smirk, working with Suschitzky’s exactitude to make sure each shot is its own comic book frame.

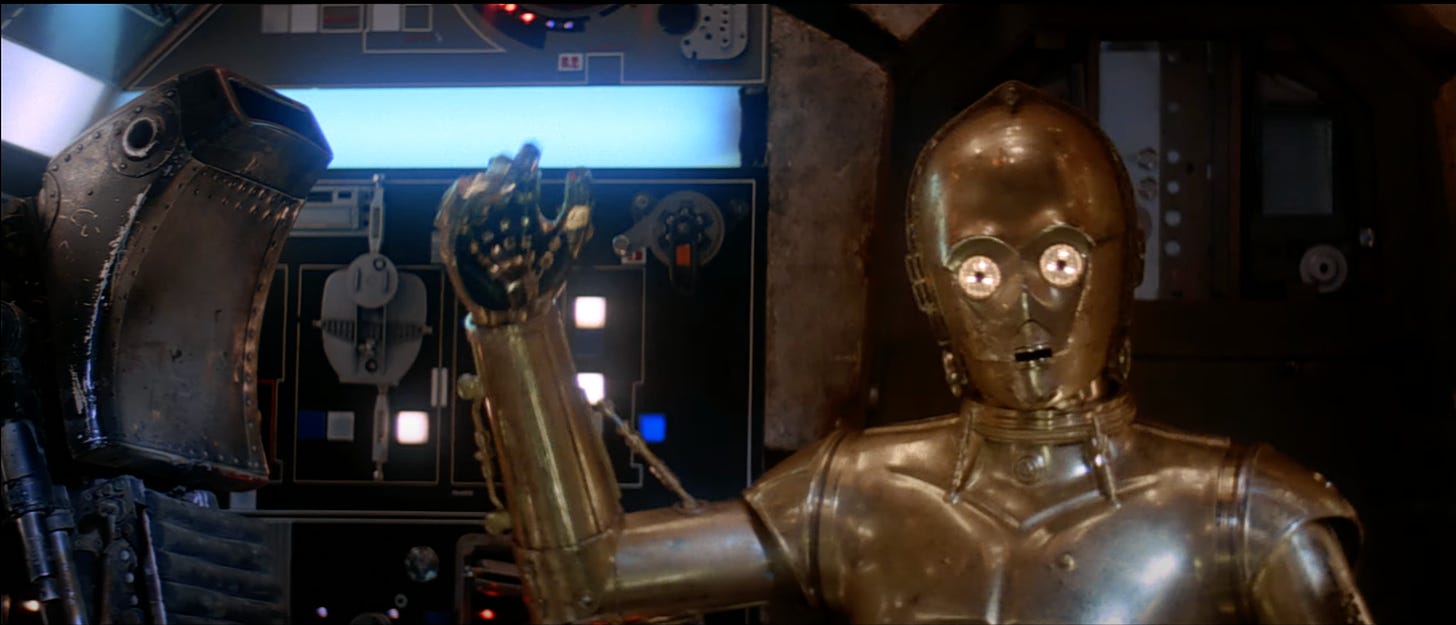

Finally, the floor is yielded to 3PO, and it’s worth noting how the staging of this beat is a subtle embodiment of the way these movies communicate with kids as well as adults. A child might be confused why a cockpit full of grownups is telling 3PO to shut up, or why they’re shoving him around - they’re all friends, right? - but a child understand that his most important statement cuts through the clutter —

— because he’s raised his hand.

(I’ve been watching this movie for four and a half decades and only just now put this together. Maybe it’s a coincidence, but when a coincidence supports the facts and vice versa, it stops being a coincidence.)

3PO’s announcement raises the stakes not only for the sequence itself, but for the remainder of the movie, as the Falcon - a symbol of duality by being the fastest ship in the galaxy that also happens to be a piece of shit - fails to live up to the first half of that reputation by embodying the second.

Han’s “We’re in trouble” is another example of multigenerational storytelling - wry understatement for adults, straightforward declaration for the kids.

A quick pop back outside (more right-to-left action), and to remind us that while the dead hyperdrive is the newest problem, the older problems still persist.

(I’m well aware, by the way, that I came here to talk about the Asteroid Field sequence, and haven’t even gotten to the asteroids yet. I did say things were gonna get granular…)

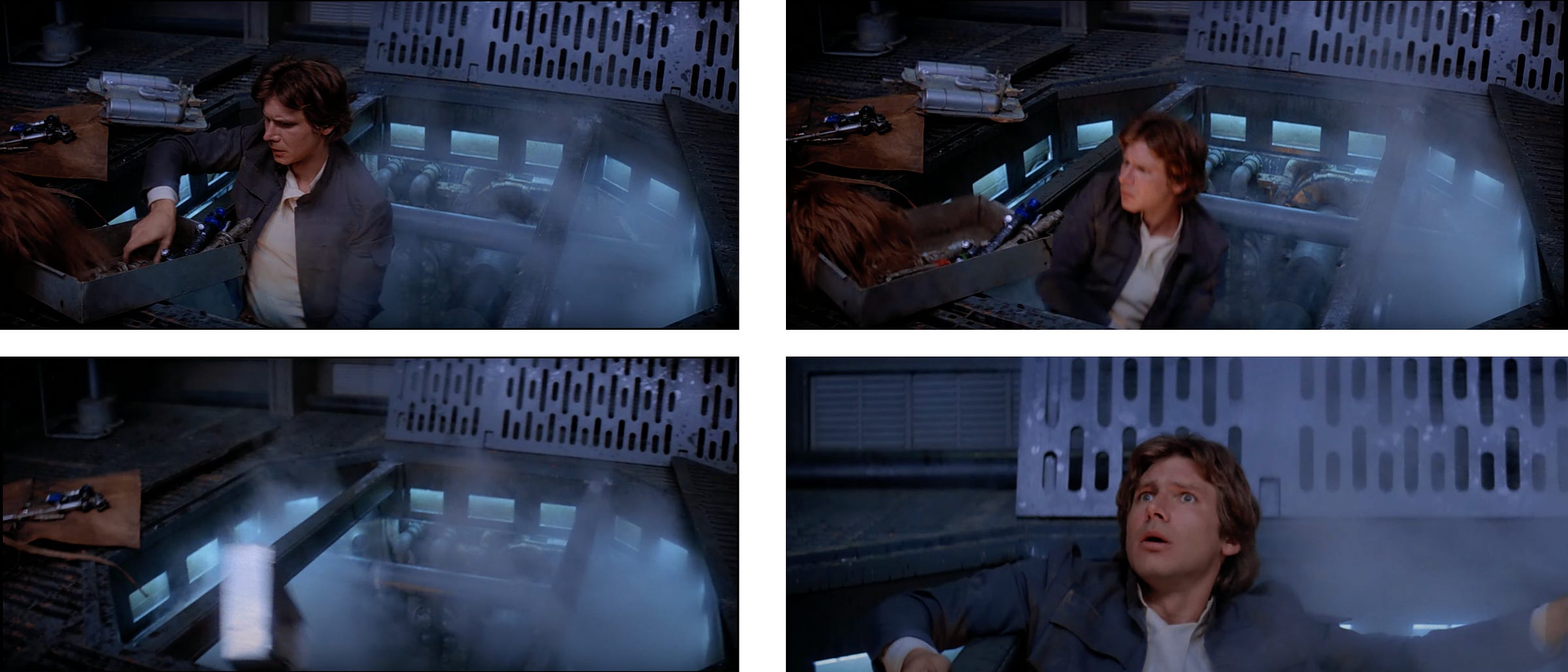

Back aboard the Falcon, we’re in the cargo bay, where Han and Chewie are already hard at work trying to fix the hyperdrive, of course while still being chased. I don’t think I saw fixing-the-vehicle-while-evading-capture done again (or so well) until Mad Max Fury Road, but somebody check my math for me on that?

We get more examples of this sequence’s use of reoriented axes (Han’s contortions in the subflooring) and in medias res action - Kershner & co. get a laugh cutting straight to Han already tangled in the pipes, rather than spend time on how he got here. (Contrast this with the comparative shoe-leather of Han and Luke climbing into the turret guns in ANH, or for that matter, the prequels, which feel like 90% shoe-leather).

Six shots in, a tracking master gives us our bearings in the scene. For all the heightening story tension, the camerawork and editing remain measured and even - were it not for the pinball-hysteria of Williams’s score, the whole thing would feel downright civilized. Instead, the score clues us into what’s going on under the surface for Han - the strain of responsibility he feels for his ship and makeshift crew, the interior grinding of hope against desperation.

Ok, now we get to our first implication of asteroids in a three-beat visual gag (culminating in Han’s O.S. “OWWWW”), before reframing for him to feel the second asteroid impact. The reframing is notable - his physical position hasn’t changed, but his framing is steadier, more eye-level as he comes to the decisive conclusion they’ve been hit; the higher angle in the in the OWWWW gag has him literally in over his head.

Leia summons Han, and a graceful tilt-and-pan pulls him out of the subflooring, and back toward the cockpit. Duty calls, and he answers, quite literally rising to the occasion.

(I know “rising to the occasion” may feel like a reach, but I stand by it; in a richly-designed movie like this, every decision is deliberate, and means something. Han could have been working anywhere in the cargo bay - behind the wall, on the ceiling, what have you - the choice to put him under the floor and have him rise out of it not only harmonizes with his eventual fate late in the second act, but enables action with visual meaning, not just business for business’s sake.)

Resetting to the cockpit, we get an establishing shot of our newest threat (added to the Imperial ships and the no-go hyperdrive):

The Asteroid Field.

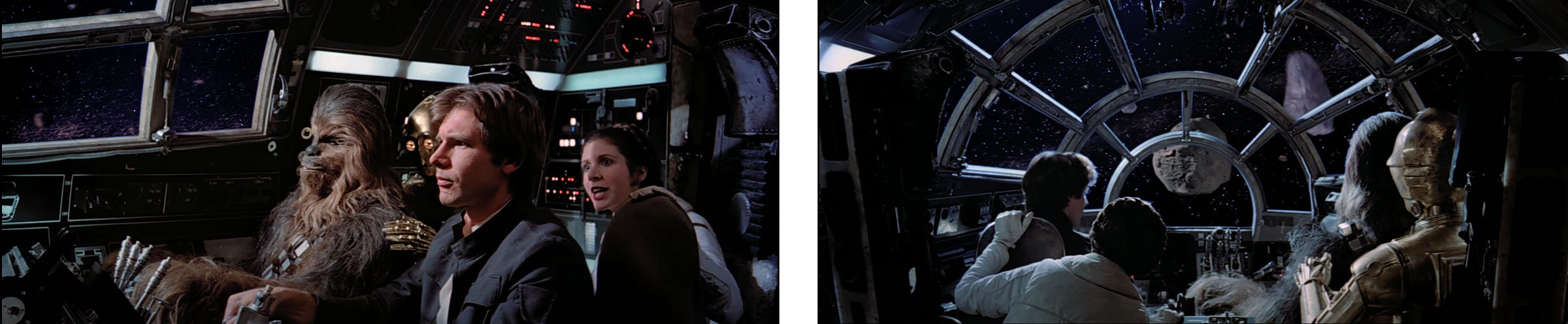

Han, still perturbed, moves into action - more steadily and on-point than we saw him a moment ago, tangled in pipes and steam. For Han, escaping the Empire is a matter of urgent necessity; the failed hyperdrive, a reflection of his inability to keep his ship whole; but an asteroid field? That’s force majeure, and it’s too irresistible a force to be reckoned with rationally.

And reckoning with things irrationally is basically where Han lives and breathes.

So while I’m sure he’d rather a functional ship without wolves on the bumper, he realizes in a bit of instantaneous calculus that the insanity ahead of him isn’t a third problem - it’s a solution for the first two. Ford’s body language tells the whole story here - a quick wry frown before he sits into the captain’s chair, and from then on, he’s purely down to business, even while Leia and 3PO can barely fathom what’s going on.

The front-seat view roots us in Han’s POV as well as bringing the asteroids ever closer, as Williams’s horns escalate into a panic.

Time for a quick deep breath before the plunge —

— and we’re in it now. More axial fun / compositing nightmare, making sure that each VFX shot counts, but also showing us that Han’s not tiptoeing here, he’s strutting. Not for kicks, not for clout, but because that’s what the situation needs.

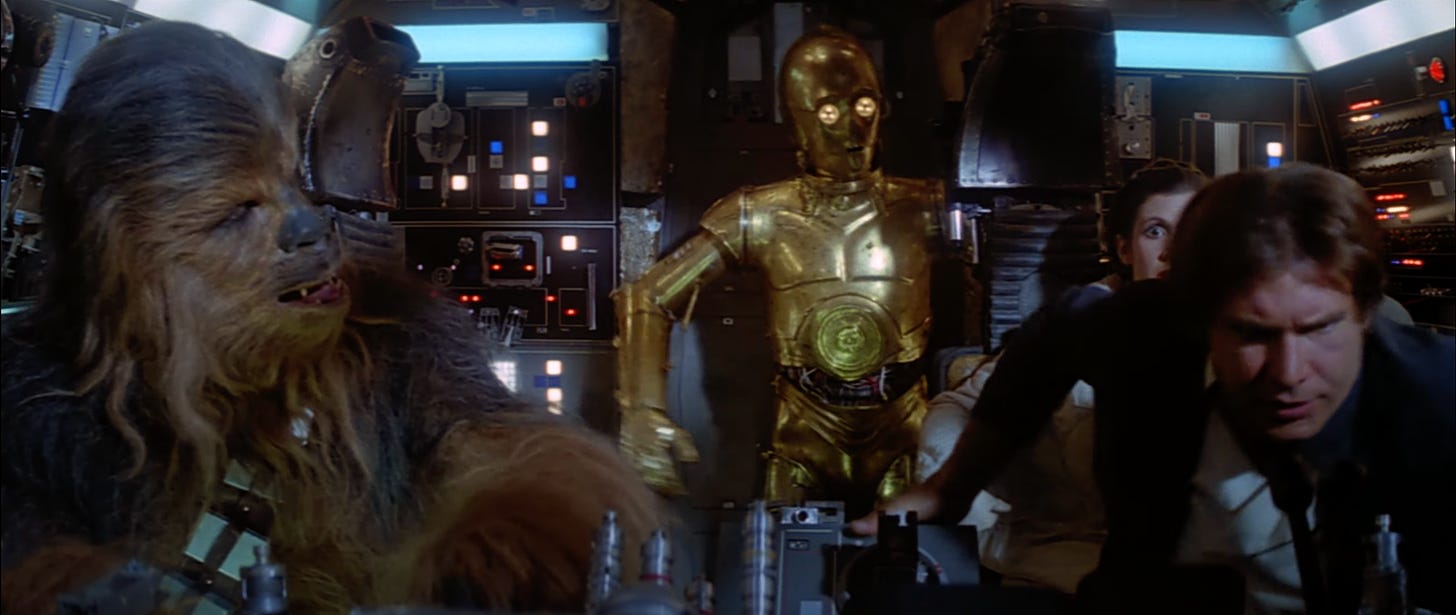

Back into the cockpit for three lines of dialogue:

Leia’s wry zinger, returning to the quartet framing we last saw visually connects this cockpit beat to the previous one.

3PO’s recitation of the odds, where a quick reorientation brings us a new angle that gives the lie to Han and Chewie’s steely stoicism in the head-on view, and groups our family unit in the f.g. while keeping the omnipresent threat in the frame.

Then, Han’s legendary rejoinder, bringing us into the tightest framing of the trio of shots, steadily, rhythmically working inward.

It’s telling, by the way, that 3PO would stand over Han’s shoulder, when his more accustomed spot in the cockpit is the passenger seat behind Chewie (see the hand-raised shot). It’s a sequence full of characters at odds with themselves - Han, a double-fugitive trying to do the right thing; Leia, unwittingly falling for the guy who’s about to get them killed - so why should 3PO, torn between the Jiminy Cricket need to be heard, and the self-preservational instinct to stay near the most protective force in the cockpit, be any different?

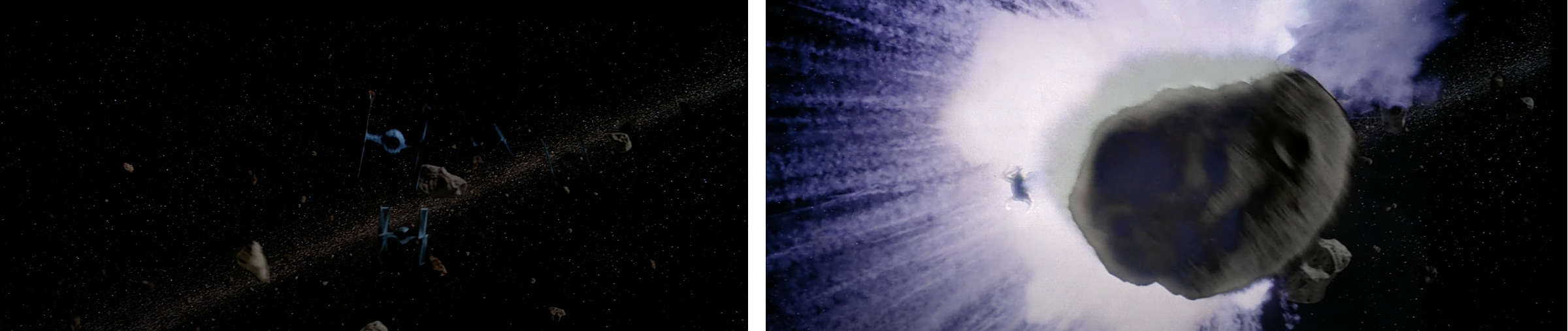

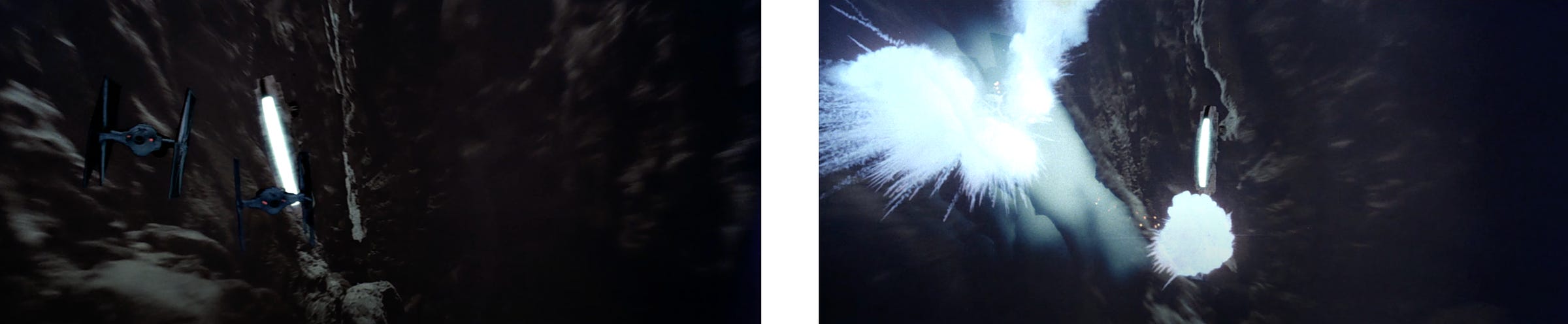

Back outside for more right-to-left action, the Falcon (pardon the expression) cresting a massive asteroid, the four TIEs still in pursuit.

A quick reverse angle establishes the Falcon as out of that gauntlet before —

— showing us that one of the TIEs isn’t so lucky.

Three beats:

Head-On: the Falcon dodges the Asteroid

Rear Angle: the Falcon is safe

Head-On: the TIE gets hit

The next trio of beats act as a shuffled replay, complementing and riffing on the progression:

Head-On: the Falcon dodges the asteroid

Head-On: the TIE takes the hit

Rear Angle: the TIE isn’t safe

Now that we know that the Falcon is managing its way through the asteroids, we cut back into the cockpit to see how they’re managing, and it turns out: not well.

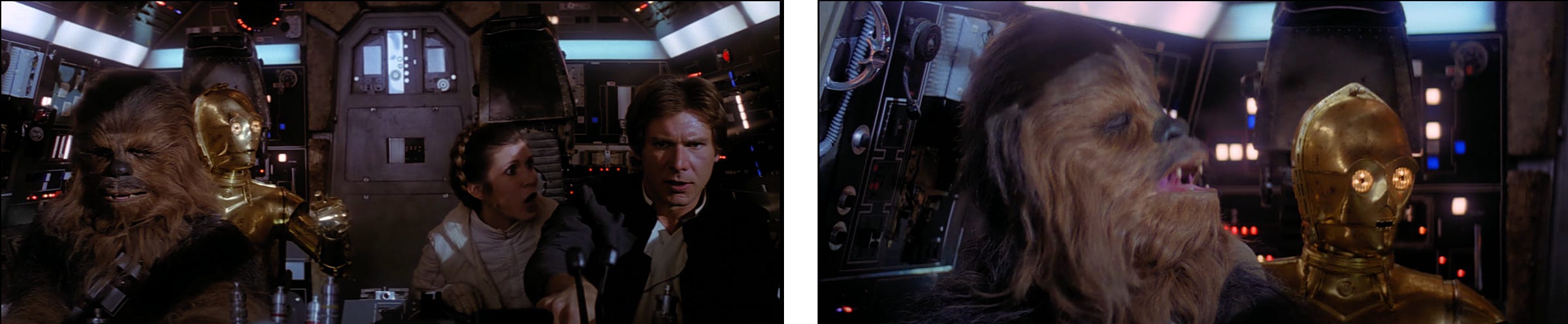

Han is visibly shaken. Even Chewie, the last to realize it’s going south, definitely realizes it’s going south. The ad hoc solution to blast their way through big asteroids shows that that just makes thousands of little asteroids (as if preemptively answering the proto-internet nitpick of “why don’t they just blast their way through?”)

Leia, the voice of reason, urges Han to reconsider their current course; it’s notable that she’s framed to appear over his left shoulder, while 3PO was framed over Han’s right shoulder while spouting the odds Han famously doesn’t care about.

Of course, when Han’s agreement with Leia coalesces into his plan to get closer to one of “the big ones” (telling us that we only thought we’d seen “big ones” so far), the reframing puts Leia over his right shoulder - the side he ignores.

Han’s plan unsurprisingly meets mixed reviews - even Chewie breaks his silence.

Resetting outside once more, we’re given our new topography and trajectory, and a reminder that there are still two TIEs in pursuit.

Here we see evidence of the sequence’s formal mastery, taking the time at the start of each new beat to set the table in terms of situation and geography —

— and to reintroduce the cast of characters into that situation.

Until now, the Falcon’s been able to keep a lead on the TIEs, but as we ramp into the climax, that lead dwindles, as the TIEs enter the pursuit frame lasers-first.

And then the bottom drops out, as the nesting doll of thrills keeps finding new ways to shock and delight.

A panning shot (from, you guessed it, right to left) pulls the action across the crater floor, toward —

— the canyon —

— where a mixture of cartoon logic and smart ship design lets the Falcon bank through the coin-slot gap that the square-framed TIEs can’t.

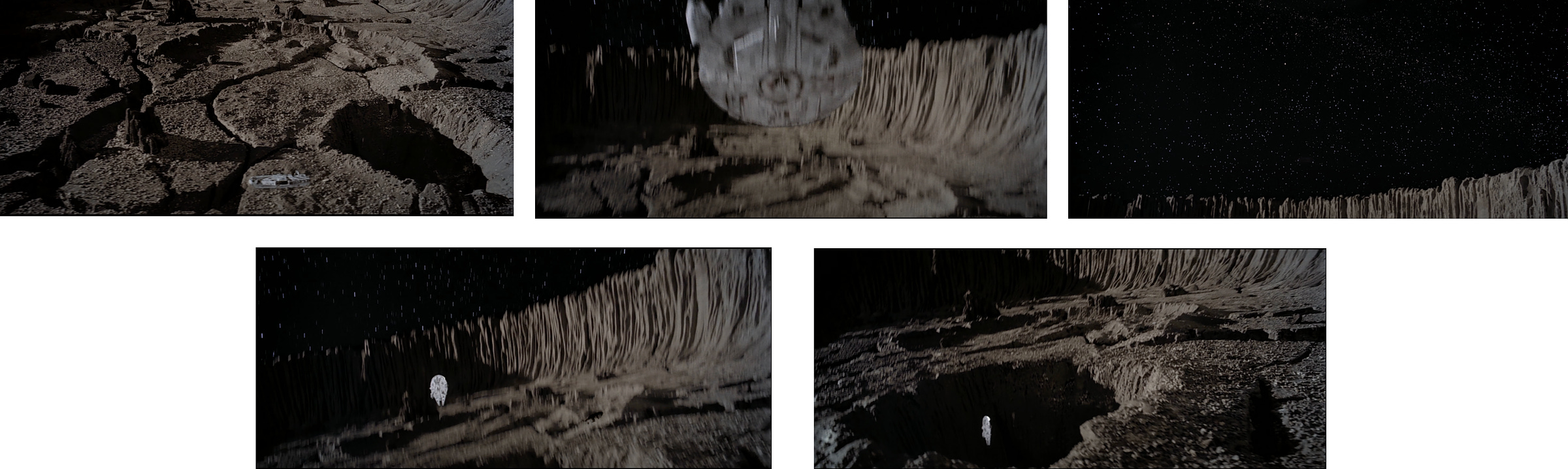

Aaaaand, victory lap.

A chorus of cheery, descending flutes (closing the book on the rising, minor-key alarm that began the sequence) escorts the Falcon out of the canyon, segueing into the “Han Solo and the Princess” love motif.

Rather than disrupt the tone and pace of the sequence with some sort of “My hero!” reaction shot that would turn Leia into Olive Oyl, the score does the heavy lifting of establishing the sequence’s most important change: recognizing Han’s heroism here, Leia sees him in a new light; she’s begun to fall for him.

But of course, they’re not out of the woods yet - the Empire still owns more TIE fighters, not to mention Star Destroyers, not to mention they’re still in the middle of an asteroid field without a working hyperdrive.

The fact that Han’s not celebrating the short-term win stands him apart from the Han of ANH, ready to call it a day after escaping a couple of TIE fighters; he’s internalized Leia’s “It’s not over yet,” and he’s no longer the guy to snap back “It is for me, sister.” He’s only a few paces ahead of her on the path, but he’s falling for her, too. (But then, when hasn’t he been?)

Han’s already cooking on a level the others aren’t, spotting a place to hide while Leia and 3PO can only look on and shrug.

With a glorious grace-note of a backflip (presaging Maverick’s fly-by by half a decade), Han guides them to purported safety, and in a more naïve telling of this story, the sequence would understandably end here on this feel-good curlicue.

But that’s not this movie. And like every movie, this one trains you how to watch it while you watch it. Lucas, Kershner, Kasdan, et. al. are preparing you to accept some hard truths and harder defeats that are heading down the pike.

The lush romanticism of Han & Leia’s theme is dismantled by six descending brass notes that usher in tense strings as the Falcon creeps into the “cave.”

We’re back in the cockpit, now bathed in Suschitzky’s splendid blues and purples, the framing tighter, more claustrophobic, the lighting murkier than when we’ve previously seen this angle. The horrible truth dawns: every victory is only “for now.”

Realizing that their newfound safety may not be all that safe, with nowhere to go but onward, deeper into the cave.

III. Can’t Argue With That

If you’ve read this far and have any questions for me, I’m sure high among them is: why this sequence? Apart from having a lot to say about it - and, get me started, I can do this with almost anything - what is it about this that stands out for me, particularly in a movie full of methodically planned, technically challenging, emotionally lush sequences?

I suppose I could just as easily have dissected the AT-AT attack, but that trades in far simpler emotional states, namely dread and failure, and while it’s a technical marvel and a thrill to watch, it lacks that undertow of fate for me that the Asteroid Field deftly threads through its action beats.

The romantic relationship that will determine the fate of the galaxy for generations to come is codified within these three minutes, and it’s not even the foreground element. I suppose a prequel apologist could argue that Padme and Anakin’s love had more dire consequences for the saga, but their romance was cemented in fields and by the fireside, the province of the melodrama, not the space opera.

At any rate, I’m not here to get lost in the labyrinth of canon, and your mileage on preferred Star Warses can certainly vary, but something an audience is told will never hold a candle to what an audience can be made to feel.

Beyond the content of this sequence - which I clearly have a few thoughts about - I’m knocked out by its form. Essentially, it’s a standalone three-act story nested within a larger three-act story:

Act One: Pursued by Star Destroyers & TIEs

Act Two: The Hyperdrive doesn’t work. (Midpoint: Asteroid Field!)

Act Three: The Big One

Part of its magic is that the sequence thrives on the tension between its frantic content and calm, patient form.

For me, for the things I look for in a movie, this sequence is the total package. I suppose that’s not surprising, since this is a formative sequence for me, and one against which subsequent movies have been judged, reasonably comparable or not.

What moves me about the sequence isn’t just its dynamism or its VFX (though both are unimpeachable), it’s that it manages to critically further the story, and to thrillingly perpetuate Empire’s recurring theme that no good news is permanent, all in the course of a sequence so densely packed, it could spiral out of control at any moment.

The marvel of it is how close to that edge it skates without ever going over.

AG.

Note: All images are the property of LUCASFILM, LTD. No ownership implied.