This was written during the 2023 SAG/AFTRA strike, and in the immediate aftermath of the resolution of the WGA strike. The work covered here would not exist without the labor of writers and actors striving for improved working conditions and fair pay.

::

As tends to be the case, this newsletter will start with some personal reflections, observations and reminiscences, so if you’d like to go directly to the meat of the subject, please feel free to jump to II. Where There Never Was A Hat.

::

I. Look, I Made a Hat

Creativity is a tricky, distracting, lonely, distancing, isolating thing to live with - a pull, an obsession, a constant, background hum - and in past relationships, I’d found my partners less supportive than I needed of the attention I felt compelled to give to ideas I was trying to bring to fruition. I was beyond lucky to marry a woman who understood and encouraged this behavior, and suddenly, making things and sharing my life didn’t feel like either/or.

Of course, that’s by the standards of 20-odd years ago, where my creativity had really only one longform output - screenwriting. Now, my creativity tends to be more fragmented, splintered, an itch that can be scratched a thousand times a day crafting a tweet, an essay, a pic, a video - not to mention that I write and produce video content1 for a living, so there’s that - so while the individual distraction is briefer, it’s more prevalent.

On my better days, I still make time for longer, less immediate, less digital projects - a script page here, a sketchbook doodle there2 - or even the newsletter you’re reading right now, begun in part to mitigate my use of microblogging social sites, and to help retrain my brain toward longform concentration.

Depending on who you ask, creativity is easier than ever, with a wide range of tools readily available to make shit with. And look, I’m hardly a luddite - I may have trained on a Steenbeck flatbed editor in college, but obviously any videos I make now are made in Premiere, typically featuring graphic elements created in Photoshop and video captured digitally.

But to my mind, there are tools and there are shortcuts. And who, when faced with the opportunity to make art, would bother with the laborious, lugubrious part of it when you no longer have to?

Yeah, I’m talking about Generative A.I. / Large Language Models, referred to from here on in as A.I. for concision and clarity.

There’s a lyric in Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine’s Sunday in the Park with George that, to me, encapsulates the point of creativity better than any other expression:

Look, I made a hat

Where there never was a hat.

In his indispensable lyric-and-essay collections3, Sondheim describes the song as “reflect(ing) an emotional experience shared by everybody to some degree or other, but more keenly and more often by creative artists.” I’m flattering myself to think Sondheim was talking about me4, but his definition is expansive enough that I feel included by it, at least enough to have Some Thoughts about it.

II. Where There Never Was A Hat

George - a fictionalized version of pointillist Georges Seurat - ranks high among Sondheim’s rogues’ gallery of obsessive perfectionists, whether we’re discussing Sweeney Todd’s single-minded focus on revenge, or Franklin Shepard’s relentless need to prioritize success over personal relationships. I can’t say this with any biographical certainty, but to me, George has always felt like the clearest distillation of Sondheim’s own compulsions, starting the show with his pronouncement of first-principles.

These principles balance the breadth of George’s oft-invoked obsessions - art, beauty - acting as the architectural joists on which he builds his work, and to take a step back, on which the show about him is built.

George struggles to balance his commitment to developing radical new techniques of expression and recreation with his relationship with Dot, his devoted model. Really, to be fair, it’s Dot who struggles with the balance - George has difficulty seeing Dot as a person with wants and needs of her own. George never quite stoops to treating Dot with active dismissal, so much as he doesn’t have the RAM in his head to take Dot to the follies as promised and to finish painting a hat - one small detail in a massive canvas rendering the eponymous Sunday into countless dots.

For Dot, passive neglect is just as bad, and she leaves George for a less complicated, more attentive lover, at first making a spectacle of her new affair to get a rise out of George, later marrying the new man in part to explain her pregnancy (by George).

Dot’s protest-too-much showstopper (Everybody Loves Louis) seems not to hit George’s radar, busy as he is sketching the park’s denizens going about their business “on an ordinary Sunday.”

But after the applause subsides, and the cast exits, George is left alone with his sketchpad (and a dog, his audience-of-one), seemingly as he prefers it. And for the first time in the show, George expresses himself not in a clipped staccato, but with a lyricism he’s only hinted at until now.

Here are my two favorite versions of the song, first by Mandy Patinkin in the role he created on Broadway in 1984 …

… and then by Jake Gyllenhaal in this promo5 for the 2017 revival:

The piece begins small, almost furtive - all low woodwinds and George’s falsetto, as he reviews the sketches on his pad, reiterating other people’s lines from earlier, eavesdropping on their Sundays spent in the park:

Mademoiselles … (cribbed from two soldiers hitting on a couple of shopgirls)

You and me, pal … (an ironic sentiment of togetherness from a boatman essentially telling George to fuck off)

Second bottle … ah, she looks for me … (a wife eyeing how much her husband’s had to drink; the husband trying to link with his side-piece)

Bonnet flapping … yapping … ruff! … chicken … pastry … (George’s own assessments, mixing with his commentary from a dog’s POV)

Then, a key change brings George into a lower vocal register, and his own perspective:

Yes, she looks for me (“she” = Dot)

Good

Let her look for me to tell me why she left me

This soliloquy plays out using only four notes, descending, then failing to ascend, George getting lost in his own thoughts.

As I always knew she would

I had thought she understood

They have never understood

And no reason that they should

The first two lines stick to the same four thoughts, cementing George’s self-fulfilling prophecy of abandonment, then expanding to add a fifth note to the proceedings on “have” and “no” in the next two lines, making the drop to “never” and “reason” all the more precipitous as George gets mired in his own defeatist swamp.

But if anybody could …

Here, the melody starts to brighten, starting with the same first two notes as the two lines before, but then climbing into a new register on “anybody,” as George indulges the fantasy of a partner who could be a partner, without feeling like a resentfully neglected accessory.

His line of thought sweetening, George turns to the matter at hand, to the only matter ever at hand for him - his Work.

Finishing the hat

How you have to finish the hat

How you watch the rest of the world from a window

While you finish the hat

The Hat in this case is a synecdoche for George’s Work - a small, intricately detailed element on the large, intricately detailed canvas of this one painting, in a life he hopes will be full of large canvases and small hats.

Mapping out a sky

What you feel like, planning a sky

George’s synecdoche grows massive, almost instantaneously, turning from Hat to Sky, as he describes the impossible task of matrixing the infinite, tethering it back to the emotions such care and control bring him.

What you feel when voices that come

Through the window

Go

Until they distance and die

Until there’s nothing but sky

After “hat,” “window” is the most repeated noun in the song, used pointedly6 and with versatility7. Here, it’s a barrier, the filter through which the real world trickles, as life continues outside of his focus, without him.

And how you’re always turning back too late

From the grass or the stick

Or the dog or the light

Here he cops to his flat-footedness when trying to split his focus from the things he creates to the people around him. The four objects seem insignificant, almost random on their own, but in George’s escalating tone, they’re desperately essential. Of note, “grass” and “stick” share a note, “dog” and “light” share a higher note, as George’s focus intensifies, climbing from inanimate (grass, stick) to vital (dog) to maddeningly intangible (light).

How the kind of woman willing to wait’s

Not the kind that you want to find waiting

To return you to the night

Dizzy from the height

The melody peaks on the first line, gets mired in elliptical frustration on the second, then nearly post-coital in their sensitivity in the final couplet, as George unpacks the central paradox: it isn’t just about having someone in his life, it’s about having the right someone in his life, that enervates him.

Coming from the hat

Studying the hat

Entering the world of the hat

Reaching through the world of the hat

Like a window

Back to this one from that.

The melody returns back to ones, as George fixates through repetition on The Hat, before expanding into the near-magical act of transference that his concentration on even so simple an object can bring him.

Again, he invokes the window, this time not as a barrier, but a lens, offering perspective and insight into the intangible world he simultaneously creates and discovers.

Studying a face

Stepping back to look at a face

Leaves a little space in the way like a window

George’s work is one of the avenues by which he engages with people, but always with “a little space” between - they’re his subject and object, but it’s not a reciprocal human relationship.

But to see —

It’s the only way to see

I’ve always read a double-meaning into this couplet - George is either stating then reinforcing the notion of “to see” or he means that the person he seeks will “see (that) it’s the only way to see” - that distance and perspective are essential to his work, and must be respected.

And when the woman that you wanted goes

You can say to yourself, “Well, I give what I give”

But the woman who won’t wait for you knows

That however you live

There’s a part of you always standing by

Mapping out the sky

One of my favorite touches in this song is how George alters the definition of “woman” based on the use of the word:

When the woman that you wanted describes an object, a goal; The woman who won’t wait for you describes a person. To George, women achieve personhood through agency, but the only agency he experiences is their choosing to leave.8

He fears that the only legacy, the only lasting impression he leaves on a departing partner, is his detachment. And from the confines of his detachment, he has no way of confirming whether this is true or not, though certainly when Dot later confronts him for his aloofness, he gets a pretty solid earful of the limitations of his own estimation of himself.

Finishing a hat

Starting on a hat

Finishing a hat …

The cycle will continue, with or without other people. George then turns to the dog, showing what he has to show for all this turmoil:

Look, I made a hat …

Where there never was a hat.

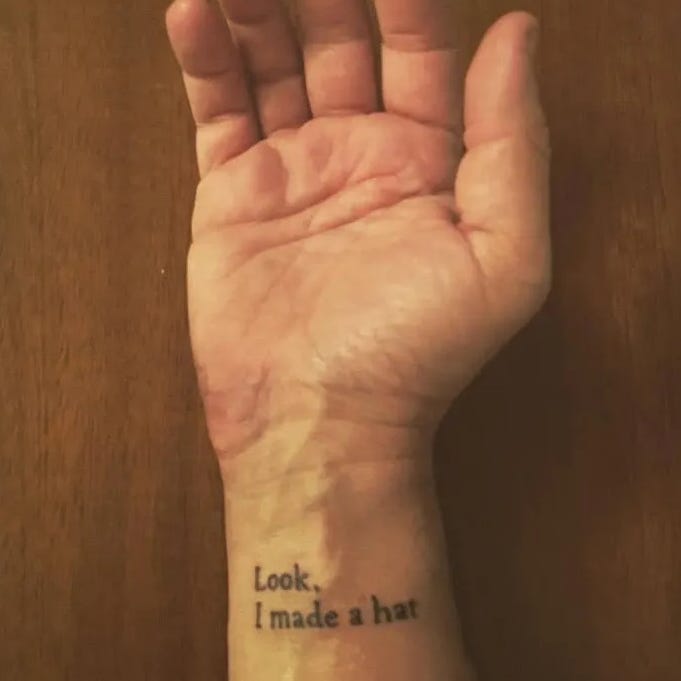

It’s a dictum that means the world to me - it’s literally tattooed inside my right wrist9 - that, reduced from the conclusion of a thesis to a catchphrase, could very easily be misappropriated by the A.I. evangelists of the world to justify the kind of creation they deal in - the magic trick of turning nothing into something, even if we’re straining the definition of “something” in what’s been created.

Because while, yes, the notion distills to “something that wasn’t there is there,” you have to ignore the three minutes and change before it not to realize that the beauty comes, in part, from the labor.

For George, there’s no ecstasy without agony. And I’m not saying that that’s true for every creative person on every creative project, but even in the bare-minimum act of creation/creativity, there’s no fruit of labor without labor. It’s right there on the label.

III. Putting It Together

A few months back, I bought a sketchbook. Not to become an introspective pointillist, because in fact I've never been able to draw for shit and still can't, but I was looking for more ways to keep busy that didn't involve picking up my phone.

Every couple of days, I'll open up the book and, I don't know, doodle a robot, or try and replicate something I see in real life (I spent an hour on the steps of the Met last spring sketching the brownstone across 5th Avenue; the drawing is no good, but it made me think about detail, perspective - to really contemplate and concentrate on what I was looking at and trying to recreate).

My drawings are rarely any good - there's nothing in there that you'd call art, but that's only if you measure art by the result and not the process. And the process holds infinite value.

I don't sketch with an eye on sharing my work - again, can't call it art - but because I like spending an hour trying and failing and erasing and re-drawing, and failing again, and maybe by the end of that hour, having gotten incrementally better, or at least carved a few new pathways in my brain for how to look at or think about an object, all for the cost of a blank book and a couple of pencils and erasers.

Here’s a Calvin and Hobbes comic, not made by Bill Watterson, but by a comic artist who, as you can see, did it using DALL-E 3. And I'll level with you, stick this in the pages of a C&H compendium, yeah, maybe it blends in with the crowd, even while it's not possessed of any insight or narrative rhythm or syntax or copy-editing.

More critically, it's not particularly funny, unless you count the irony of an AI-generated comic about how delegating tasks to a smart machine leads inexorably to explosive failure.

It expresses nothing. It reflects nothing. I can't tell you anything about the person behind it except that they like Calvin and Hobbes, and they like feeding material they didn't create into an engine they didn't make to yield something you can never hold in your hand.

Its most significant point of tangibility is as an embodiment of Ian Malcolm’s axiom “You stood on the shoulders of geniuses to accomplish something as fast as you could.”

Look, I haven't read Brown Bread CoMix's work, and I genuinely hope their original works showcase a passion and talent that elude my own sketchbook fumbling, but I'll tell you this, and your mileage is very free to vary, of course:

I would much rather spend an hour concentrating on making something not ready for presentation than a couple of minutes plugging data prompts into a plagiarism engine for a finished product that barely meets the standard of *existence*, let alone art.

As I write this, one craft guild has just won a months-long strike to keep A.I. out of the screenwriting business, and another craft guild is at the table trying to keep actors, living or dead, in the business of acting.

And look, I’m not saying ALL A.I. IS BAD - if it’s a tool, then like any tool it can be applied responsibly and ethically - only that we seem to be rushing headlong into adopting it into widespread use without any real consideration for what gets lost along the way, both in terms of the human experience of truly making something out of nothing, sometimes at great personal cost, but in consideration of what comes next as we relentlessly feed centuries of creativity to machinery learning at a geometric rate.

As I’ve said above, art doesn’t have to be agonizing to make, but it should take labor. Not for nothing are they called works of art, after all. And while there’s great appeal in “leveling the playing field” in terms of who “gets” to be an artist, in my opinion, some playing fields should stay un-level. Do I think art or entertainment should remain gatekept by a few oligarchical multi-national corporations? No, but making a hard thing easier is different than making it easy.

And that is the state of the art.

AG.

NOTE: All images and music are the property of their copyright-holders. No ownership implied.

Oh, that word.

More on that later.

Finishing the Hat and Look I Made a Hat

Though, GOD, it sure does feel like he’s talking to me…

Directed by Cary Joji Fukunaga

To say that Sondheim is meticulous about his word choice feels a bit like an understatement, sure, but it’s worth pointing out, no?

Again, doi, but it’s worth saying

I don’t personally think of George as being misogynist so much as not-a-people-person, and in 1984, there was less cultural onus to scrutinize such a passage than there would be today, for good or ill; I’ll leave it to you to determine whether this turn of phrase adds up to that.

Call me a hypocrite for indulging in the kind of reduction I’m decrying by literally inking it into my skin, but if I were to get the whole thing, the conclusion would be somewhere in my armpit, so I skipped the line.