This was written during the 2023 WGA and SAG/AFTRA strikes. The work covered here would not exist without the labor of the writers and actors currently striking for improved working conditions and fair pay.

::

I’m old enough to know two inextricable facts:

Starting new things is hard

Starting new things, already hard to do, is even harder to do without a mentor

Now, “mentor” is a tarp of a term, blanketing all manner of definitions, but when I started these essays way back in (squints) two weeks ago, I knew they felt gratifying to write, but also knew that my gratification wasn’t enough. So, I reached out to my internet friend, the dazzlingly talented film writer Gena Radcliffe to ask her opinion of my first couple of essays.

To my relief, her feedback was not only incredibly complimentary (always nice to hear!) but thorough and considered, which I’m also old enough to appreciate is the only kind of feedback worth a damn.

Chief among the feedback’s virtues: timeliness. Not that I expect someone I’ve hit up for a favor to work on my timetable, but more critically, the turnaround on the feedback allowed me to disrupt my process and revise my thinking in time for this exact essay.

In her assessment, Gena suggested that the granularity of my focus had a tendency not only to be exhaustive but exhausting, and as such recommended the occasional shorter essay for people who maybe don’t want to chop things up to the nostril-level of specificity. Good news for all of us, my ability to zoom-and-enhance on a subset of a piece of art is scalable, so today I’m pleased to introduce —

FIVE GREAT SECONDS

— where I home in1 on a piece of minutia that’s caught my attention and sent my mind spiraling into extrapolatory cartwheels where I invent words like “extrapolatory.”

Because of how small these details can be, I’ll be scaling down my essays on them, if not my obsession with them, to a more manageable size, ballpark a thousand words or so.

Today, I’m going to lead with a confession:

I used to not like Brad Pitt. I thought he was bad at acting.

Now, in fairness to that assessment, I was a teenager (so, dumb) when Pitt first started popping up in things, so I took all of his performances as read, instead of considering them for the body of work they contributed to.

But based on his work in Cool World (unenviably carrying a rickety, horny script through a technologically challenging shooting process), Legends of the Fall (cast for his romance novel looks), and a few other small roles (True Romance, Thelma & Louise) where my teenager’s disinclination for nuance took them at face value, thinking less that he was playing dumb or wooden or pretty, and assuming he was just dumb and wooden and pretty.

All that eventually changed, particularly as his growing clout opened up roles that more fully let him showcase his talents, and honestly, it was nice to see something finally go right for the popular, good-looking guy with abs for days.

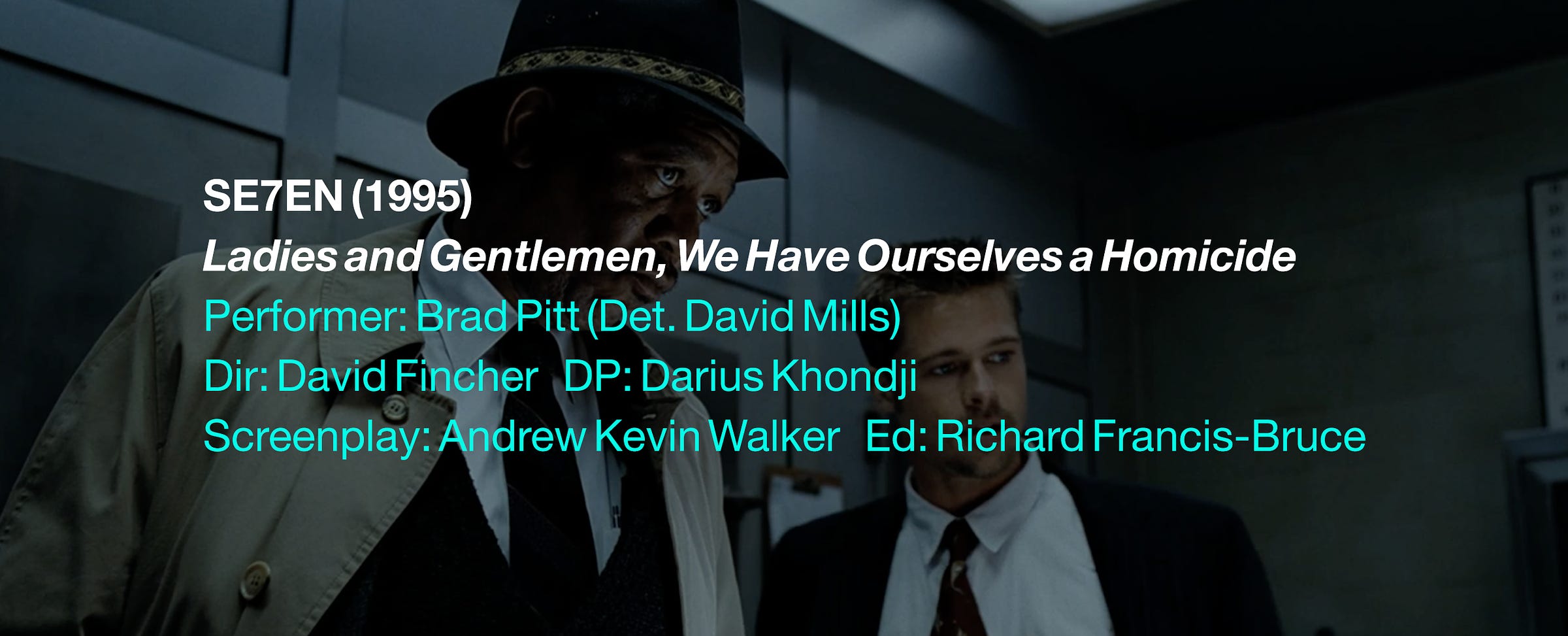

My worst miscalculation came with 1995’s Se7en, Pitt’s first partnership with David Fincher, where I mistook the brash naïveté of Pitt’s Det. David Mills for Pitt’s brash naïveté.

Later, I revisited the movie, and realized I was wrong. Brad Pitt isn’t always great, exactly - he tends to come across as bored when he’s cast primarily for his matinee idol looks - but he’s more interesting than I’d given him credit for, which came to me in the crafting of one specific beat.

From their first meeting, Mills bristles against his would-be mentor, Det. William Somerset (Morgan Freeman), taking him for aloof and detached, already one foot out the door in his fabled last week before retirement. Somerset is those things, but more, though to Mills’s new-in-town eyes, that just makes him a dick.

That said, Mills is a decent cop2, and the better part of his frustration with Somerset comes from the older detective’s unwillingness to teach, and by extension, inability to approve of Mills as student.

The marketing campaign managed to get mileage out of Mills’s line “Ladies and gentlemen, we have ourselves a homicide”; the line has a modicum of style, of attitude, and does a decent job of establishing Se7en’s policier milieu, relying on movie-cop familiarity to get audiences in the door for Fincher’s relentlessly (and thrillingly) grim morality tale.

In the context of the movie, though, a few key choices by Fincher, Freeman, and Pitt make something much more telling out of the fairly standard cop-movie line.

I can’t speak to how screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker intended the line to play - whether it was meant to be cop-jargon boilerplate or something more - and in the hands of another creative team, it could have stayed just that.

Instead, the scene holds for a silent beat, just long enough for Somerset to look at Mills, and Mills back to Somerset.

Somerset’s look asks if Mills is for real with his proto-CSI: Miami zinger. Mills’s look asks if Somerset’s buying it.

This one beat - a pair of simple, punctuative glances - were enough to tell me that what I’d taken for an actor’s limitations were actually his choices and tool. These were Pitt’s means of sketching Mills’ confidence as a veneer, taking time and care to plant the insecurity underneath.

Later, when Mills’s confidence cracks and his insecurity runs riot, to personally and professionally ruinous outcomes, we buy it because Pitt et. al. put in the work to make sure it would track.

By that point, it’s too late for Somerset’s mentor to rein Mills in. Feedback and encouragement, it seems, can arrive too late to disrupt the process.

AG.

Note: All images property of NEW LINE CINEMA. No ownership implied.

You can either “home in” on something which means to focus, or “hone” something, which means to sharpen, but you can’t “hone in” on something. So if you’ve been saying it that way, stop saying it that way.

In the context of the movie, that is; we don’t have to bring my personal feelings on the profession of policing into this.