As tends to be the case, this newsletter will start with some personal reflections, observations and reminiscences - today’s subject being my favorite movie of all time, the reflections, observations and reminiscences will likely run longer and more tangentially to the subject matter than usual - so if you’d like to go directly to the meat of the subject, please feel free to jump to III. CUT TO: THE SNOWSTORM

I. A SHAKY, SPASMODIC ZOOM-IN

1994.

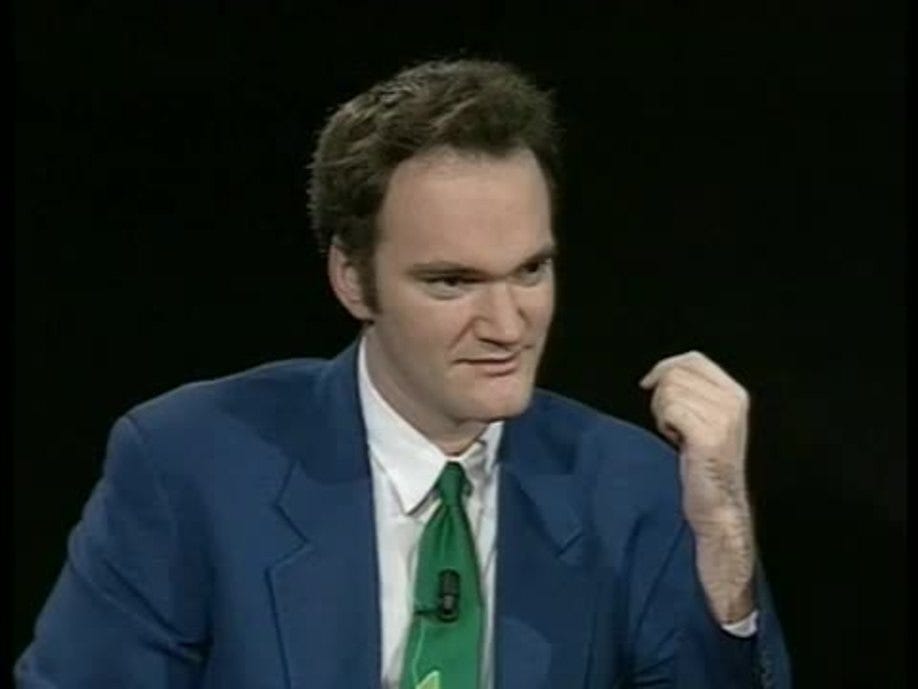

It’s winter break, my freshman year of college. We’re in Phoenix visiting my grandparents, and Quentin Tarantino - my obsession of the past year - is on Charlie Rose, in a blue blazer and green tie emblazoned with Astroboy, every inch the enfant terrible grudgingly dressing for church or Olive Garden.

Charlie is giving his typically chummy interview, showing how with-it he is by “getting down” with the current it-boy (we were decades away from knowing the extent of Charlie Rose’s “chumminess”), and at some point gets to a question about Tarantino’s influences.

QT, an artist who at that time didn’t so much wear his influences on his sleeves as much as he had sleeves made of influences, singled out living legend western-turned-crime novelist Elmore Leonard as his strongest inspiration. Leonard’s crime novels were rife with a range of wounded-to-broken criminals with a sense of pop culture appreciation and spitfire pulp turns of phrase, the sort who Tarantino’s two movies (and change) to date had made the absolute belle of the ball.

Tarantino even made plain that his first-sold screenplay True Romance (released a year and a half earlier, directed by a career-best Tony Scott) was essentially QT’s attempt at making his own Elmore Leonard novel; when considering the Detroit setting, the unlikely romance at its core, and the colorful ragtag ensemble (some of whom are introduced with no clear sense of what they’re even doing in the movie), it’s hard to deny, even if you’ve only read one or two Elmore Leonard books.

For my part, at that time, I had read none. His was a name I’d seen on bookstore shelves, but which brought an air of too grown up to me. But I figured if it’s good enough for the guy (at that point) whose every gesture and decision I’m trying to emulate, then it’s good enough for the very thinly-limned self I was carving out.

The next trip to the mall yielded zero Astroboy neckties (go figure), but two Leonard paperbacks from the B. Dalton - The Switch (1978, later adapted as 2013’s Life of Crime1), and Get Shorty (1990, already on my radar in the pipeline for a post-Pulp Fiction John Travolta’s return to stardom).

I start with The Switch, and the “parallels” to QT’s work become instantly recognizable; Mr. White’s rationalizing monologue about the ease of collateral murder if it means avoiding jailtime is more or less paraphrased from one of chief kidnapper Ordell Robbie’s soliloquies.

And while a lot things when you’re seventeen can feel like the road rising up to meet you - even when it’s really just you noticing things that have been going on for a long time - that mention on Charlie Rose felt like the starting pistol of the near-decade-long Elmore Leonard land-rush to follow, with the success of 1995’s Get Shorty as a starting pistol, followed by major filmmakers ranging from Paul Schrader (1997’s Touch) to QT himself (career highlight even in an almost-no-misses filmography, Jackie Brown) molding Leonard’s works to their vision, or sometimes molding their vision to his.

I was hooked. I’m still hooked.

1997.

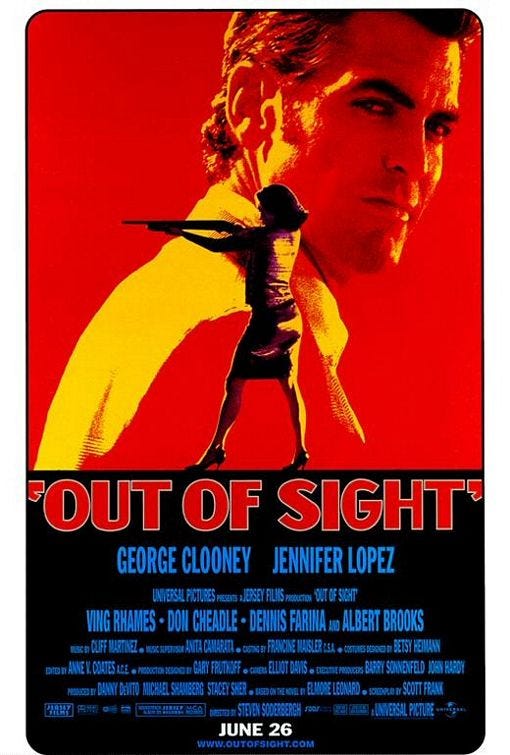

It’s summertime, and I’m my girlfriend’s +1 at the wedding in which she’s a bridesmaid. In my bag are two suits - neither summer-weight, but I only knew how to dress like a Reservoir Dog or Neil McCauley - and a bright yellow paperback of Elmore Leonard’s Out of Sight (1996), already slated for adaptation the following summer.

The starring role of career bank robber Jack Foley is set to be George Clooney, at that point an interesting and unquestionably charismatic tv star who was having trouble finding his footing as a movie star (this wedding took place nearly equidistant between the releases of Batman & Robin in June and The Peacemaker in September).

The book reads like a dream - all Elmore Leonard books do, even the lesser ones - and it’s not at all hard to see the movie in it, even as some of its sequences feel disjointed in their placement, and the overall plotting feels blunt even by the standards of a writer who ends books practically in the middle of a sentence.

But it’s impossible not to be excited at the prospect - a sense that the growing Elmore Leonard wave is about to hit a zenith, with the one-two punch over the months to come of Jackie Brown at Christmas, and Out of Sight the following summer.

1998.

It’s a Friday in June, and after I get off work at the video store, my friends and I are gonna go check out Out of Sight. A few weeks earlier, the poster for it I saw at the multiplex reawakened the previous summer’s building excitement (on hiatus while I navigated my senior year of college, and a hefty dose of Titanic fever), and even though it’s late, I’m not waiting another day for this one.

And from the JUMP, which finds Clooney’s Foley stepping into the Miami sun, spiking his necktie to the sidewalk in a potently antiestablishment “fuck you I quit” freeze frame, I’m IN.

It immediately became clear that the summer was an odd time to drop a loser noir crime-romcom - especially after it opens fourth behind Dr. Dolittle, Mulan and X-Files: Fight the Future - and despite my evangelism to the contrary, Out of Sight quietly recouped its $48MM budget with a global total of $77.5MM, and marched slowly to home video.

A few months later, I find myself working at Tower Video in the East Village (RIP), manning the DVD section, a tiny alcove in the VHS-heavy wonderland, making sure Out of Sight stayed in rotation on the monitor displaying this stunning new tech.

(Fun fact: since Out of Sight was not priced for VHS sell-thru, I brought it into my collection by swiping the For Your Consideration tape from my internship at a production company across town; you can hear me lay out the whole story on this week’s new ep of Liam Higgins’s VHS ERA, where we discuss the trailer reel at the head of the OOS tape.)

2006.

I’m a little drunk from a friend’s after-work birthday drinks, and as I make my way down 6th Avenue, I wonder, as one does, if my longtime favorite movie of all time (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) is still my favorite movie of all time.

It’s not that Butch isn’t great - it’s a masterpiece - but I’m 30, and is my favorite movie from when I’m 22 still my favorite movie? Especially when Butch is a Greatest Generation-cresting-Boomer fave, and I’m Gen X (already an “old man” among a millennial cohort at work), and shouldn’t I have something for myself?

And it occurs to me that all of the things I love about Butch Cassidy - the rumpled charisma of its leads, William Goldman’s whip-sting dialogue, Gordon Willis’s perfect use of light and color, George Roy Hill’s by-turns laid-back-and-intense direction, and over-the-hill charm of its characters - are present in spades in Out of Sight.

And from that moment, something has shifted, and whatever totemic weight stems from aligning yourself with a favorite movie now has me championing this movie as my movie.

2023.

I’ve resisted covering Out of Sight for this newsletter for a few reasons: for one thing, I wanted to get my feet under me before trying to dissect something that means so much to me; for another, when a movie is, in your eyes, without flaws, how do you choose one moment, or scene to zero in on?

So, here goes.

II. I'VE SEEN SCRIPTS WHERE I KNOW WORDS WEREN'T SPELLED RIGHT, AND THERE WAS HARDLY ANY COMMAS IN IT AT ALL.

Adaptation is hard, necessary work in bringing one medium to another. The best adaptations2 invariably understand the labor required to reshape even a strong, successful work for a new mode of storytelling; the worst offenders invariably forget that what they’re there to do is make a movie.3

Like I said, Elmore Leonard’s style is largely cinematic, stitched with prose that’s somehow at once blunt and perfectly descriptive, rich but never florid. Just the right mix of terse and colorful that lends itself to the grit and gloss brought to bear in the best adaptations of his work.

But that’s the thing: his work takes adaptation. For all their cinematic flair, his novels are novel-shaped, without the peaks and valleys needed (or often limply engaged) to make something that feels like a movie. Those who would just try to capture what’s on the page without squaring how to make it a movie are leading a doomed expedition. The best Leonard adaptations keep the voice, the tone, and the style, but do the work necessary to bring it to a new medium.

For my money, the hands-down best screenwriter at adapting Elmore Leonard is Scott Frank (Dead Again, The Queen’s Gambit, A Walk Among the Tombstone, the parts of Malice that don’t sound like Aaron Sorkin). Frank’s gift comes in preserving both the grime and charm of Leonard’s texts, while gracefully fitting them with a movie-friendly spine. Where the novel of Get Shorty ends on something of a down note (Chili Palmer survives multiple attempts on his life only to find himself in the jaws of the Hollywood machine), Frank realized the need for an upbeat, comedic ending to match the movie’s tone, and lands on a beat that brings Barry Sonnenfeld’s appetite for the ridiculous to the heights of the sublime.

Similarly, I recall holding my breath on my first viewing as Out of Sight ramped toward the novel’s rather abrupt ending … only to then continue into one of the greatest final scenes in movie history, all Frank’s creation (no spoilers; see for yourself).

Adaptation isn’t restricted to screenwriting, any more than storytelling is restricted to plot and dialogue. A director’s work is to adapt a screenplay from a page to an image; an editor’s work is to adapt a director’s raw vision into a unified work; and so on.

By that light, Out of Sight is not only the work of several authors (I mean, isn’t any movie?), but the work of several authors in beautiful, complex alignment.

Soderbergh, who followed the smash indie début of Sex, Lies and Videotape with a few high-profile indie and studio under-performers (Kafka, King of the Hill, The Underneath) before going into self-exile with a hard-reboot indie (Schizopolis). On Out of Sight, he came back noticeably refreshed, with an aggressive new sense of certainty and throwback-meets-modern style, no less saturated in the influences of 1970s New Hollywood than Tarantino, but less beholden to them.

Still a few years away from acting as his own DP and editor, Soderbergh reteamed with his Gray’s Anatomy cinematographer Eliot Davis, and brought in editor Anne V. Coates, the living legend who cut The Pirates of Penzance (1983), Murder on the Orient Express (1974), and uh, this:

I realize this has been rather lengthy for a preamble, but this is the path that led me to - and paid off in - the scene we’re discussing today.

III. CUT TO: THE SNOWSTORM

SPOILERS AHEAD. Stop reading here if you haven’t seen Out of Sight.

Out of Sight focuses on bank robber Jack Foley, jailed early on after a spur-of-the-moment bank job, where the heist goes right and the getaway goes wrong. From the jump, we see Foley as a nice (enough) guy, using his considerable charm (and the fact that he looks like George Clooney) to talk a pleasant bank teller into putting “as many hundreds, fifties and twenties” as she can fit into an envelope, all while implying her manager’s life hangs in the balance (The punchline of the scene is a tone-setting grace note).

A year later, an imprisoned Foley piggybacks on a fellow inmate (Luis Guzmán)’s jailbreak, abetted by his road dog Buddy Bragg (Ving Rhames, as delicate and vulnerable as his Marsellus Wallace was stonily opaque); in a split-second decision, they carjack and abduct U.S. Marshall Karen Sisco (a never-better Jennifer Lopez), with whom Foley, chatty and adrenalized, has a pleasant conversation while they’re making Foley’s escape, hidden in the trunk of her car. Foley, against his better judgment, catches feelings for her, in equal parts on account of their crackly conversation - ranging in topic from carceral philosophy to Faye Dunaway and Robert Redford4 - and her looking a lot like Jennifer Lopez, in a Chanel suit with a shotgun.

Look, who among us is made of stone.

Jumping ahead a few story beats - Karen is on the task force trying to capture Foley and the other escapees, while navigating her own growing feelings for him, leaving them both wondering what happens if/when they meet again - Foley and Buddy are in Detroit planning a new robbery with some shady former prison-mates (Steve Zahn, a rarely-better Don Cheadle), and Karen is there on Foley’s tail.

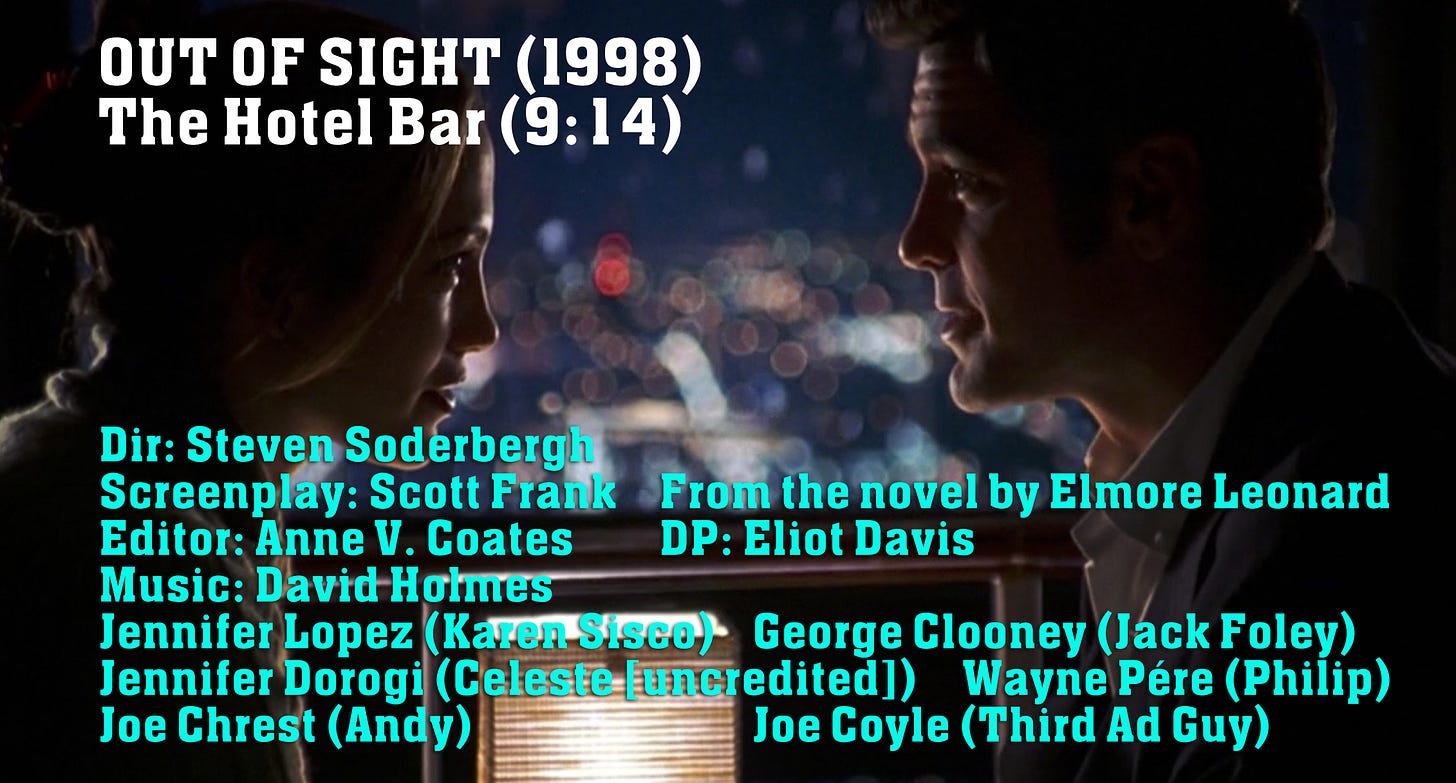

Foley, grappling with the path that has brought him here with so little to show for it, tracks Karen down to her hotel5, finding her being relentlessly hit on in the hotel bar, and the two carve out their “what if?” moment, in a scene that’s at once straight out of the book, verbatim from the script page, and yet wholly brought to cinematic life in the unified process of adaptation, production and post-production.

NOTE: This breakdown will be a bit of a mixed-media approach versus my typical approach, since I was unable to find the entire sequence in a screencapable format. While most available YouTube clips start with Foley’s entrance, the prologue to the scene is essential to its tone.

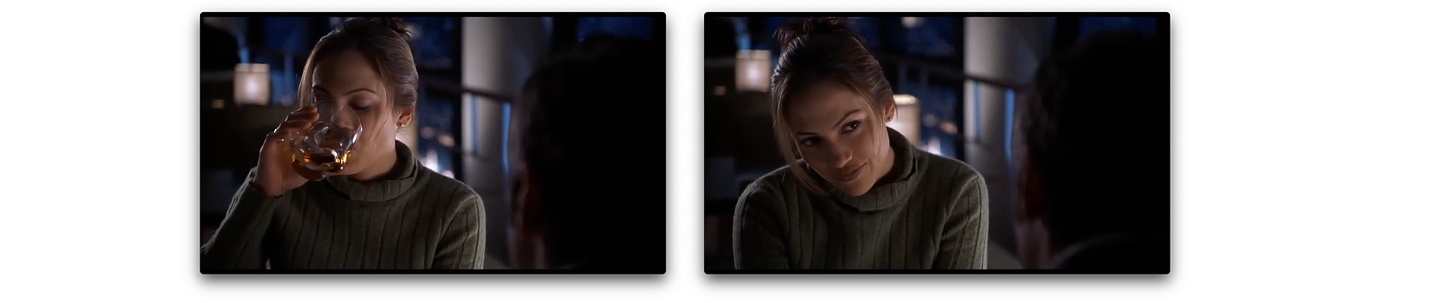

The scene opens out of focus (Soderbergh and Davis relentlessly play with focal planes and framing throughout), panning across distant city lights and falling snow, to arrive at Karen Sisco in profile, lost in thought, her face a mix of candlelight and shadow.

She orders a bourbon, water back (Jack Daniel’s in the script, made generic one assumes to avoid product placement) from the server, a pretty blonde named Celeste.

Celeste’s progress to the bar and back brings into the scene a trio of white out-of-town businessmen, who try and pay for Karen’s drink. She’d just as soon they didn’t.

When Karen turns them down (via Celeste), in a gold-medal performance of not reading the room, the men come over, one at a time, to take a run at Karen.

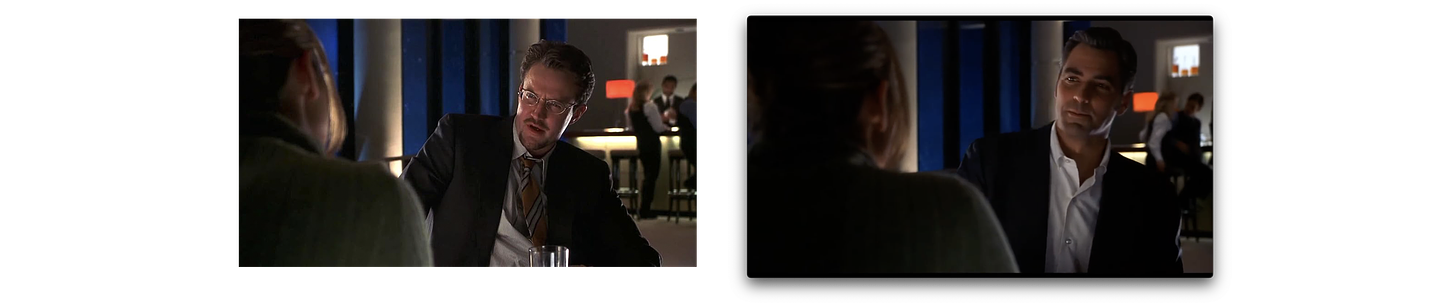

First up is Philip (Wayne Pére), whose eager grin tells us about as much as we need to know, even before he starts running his C-game on her:

I’ll say this for Philip, his bravado is on lock, and hopefully for his sake it works for him sometime down the line.

For her part, Karen is unmoved, and she does her best to be polite-but-firm.

The movie omits Karen’s “Tell you the truth” line, which could potentially cross her over from polite-but-firm into rude. But the omission isn’t about likability or how we perceive her (over an hour into things, if we’re still making up our mind about Karen, we’re in the wrong movie), but rather about giving Lopez somewhere to go across the trajectory of the scene.

Because Philip dutifully if disappointedly turns on his heel and heads back to the bar, doing a little hand-slap/tag-team tap-in with Andy (Joe Chrest). So interchangeable are these two that Davis’s camera move starts in the above low-angle of Philip, tilts down to follow him to the bar, and tilts back up with Andy’s approach to plant him right into the exact framing Philip just vacated:

Andy starts his own nervy patter, building on Philip’s smug certainty, bringing Karen into their white-collar world:

Here, Andy reads even fewer cues than Philip did, and sits in the chair opposite Karen, humblebragging about the sales trip he and his buddies are on, and while it’s all fascinating to him (a fascination he’s sure will come across to Karen), she’s less polite than she was with Philip:

Two things about Out of Sight that set up and heighten this scene:

Much is made of the suits people wear (Jack’s job interview/bank robbery attire in the first scene is an ugly houndstooth with red lining; his suit here is enough to elicit Karen’s admiration)

It’s a movie star movie about two gorgeous, charismatic movie stars doing real cops’n’robbers, shotguns and Chanel suits movie star shit.

The introduction of these whitebread lightweights trying to get on Karen’s radar is a twinkly reminder of the regular-degular real world going on around Jack and Karen’s daydream romance. Suiting both of these guys in Men’s Wearhouse’s best doesn’t do much to help their weak-sauce game, and I’m definitely not trying to shade the physical appearance of either Pére or Chrest6, but neither one of them is, y’know, George Clooney, and the movie is saying so in no uncertain terms.

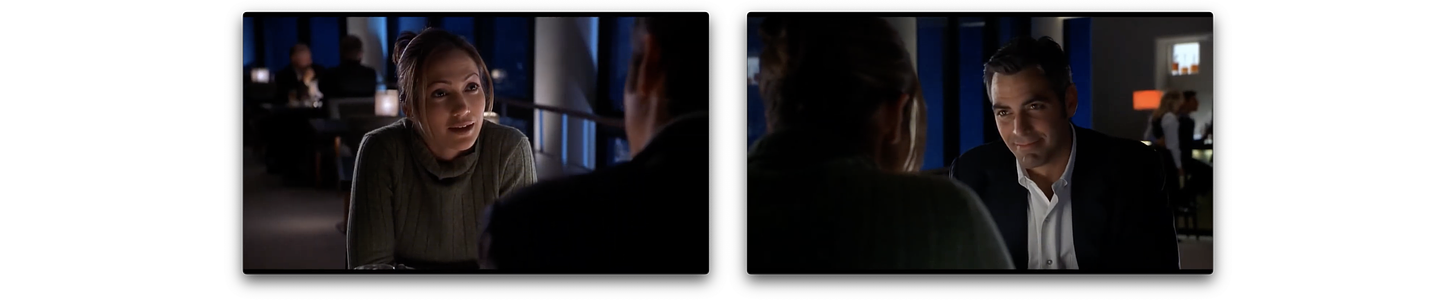

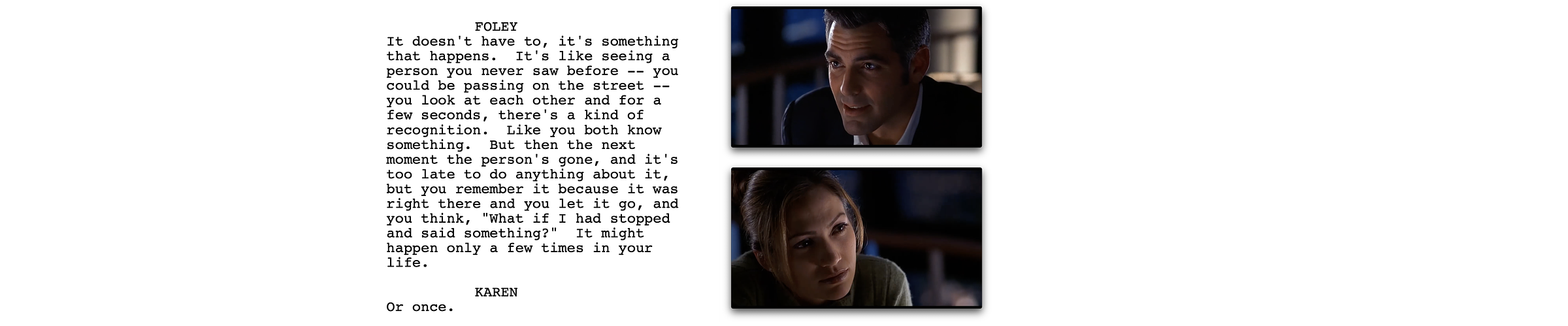

A third man approaches, but it’s not the other businessman7; it’s Foley. He enters in reflection, his arrival heralded with a click of the Zippo8 he consistently fidgets with throughout. Literally appearing out of the night sky and the snow, Foley could well be in Karen’s imagination, but we know about his Zippo, and she doesn’t. He’s very real.

Karen, face open with surprise and guarded delight, takes Foley up on the drink he offers, and we establish a non-reflective Foley in that same framing:

We see now that that framing was reverse-engineered for Clooney’s exact proportions, with Pére’s leering grin and off-center placement, and Chrest’s frame-breaking height creating a Goldilocks progression that punctuates the scene so far by landing us on Clooney, steady and symmetrical under Elliot Davis’s edge-lighting.

Karen invites him to sit, and we continue to throw dirt on the salesmen’s graves by solidifying how Jack holds a frame compared to their tilts at Karen:

Even at the same canted posture, Foley cuts a larger figure, sits straighter, and his suit fits better.

And look, there needs no ghost come from the grave to tell us George Clooney is a good-looking guy, but Soderbergh’s M.O. with this movie was to grow Clooney out of his E.R. tics and tricks, into the full-fledged, Paul Newman heavyweight movie star he was capable of being. Moments like this help undeniably engrain the notion of George Clooney, Movie Star for all to see, and the proof is in twenty-five years’ worth of pudding.

A quick handheld insert - standing apart from the fluid tilts and solid lockoffs of the scene so far, and a harbinger of things to come - has Jack slowly but decisively setting his Zippo down next to Karen’s bourbon, and friends, if you’re on this movie’s wavelength, the confident intimacy of this gesture is hhhhhhhot.

The angles stick to A-Camera / B-Camera over-the-shoulder shots as Jack settles in, taping over the same framing Andy had so discourteously occupied a moment earlier. Jack playfully introduces himself as “Gary”; Karen responds as “Celeste.”

Their game locked in, we settle into the hero framing for the scene …

… and I’m reminded of a deleted scene of Tess and Danny from Ted Griffin’s Ocean’s Eleven screenplay, a happier-times flashback described as “it’s hard not to be in love at this table.”9

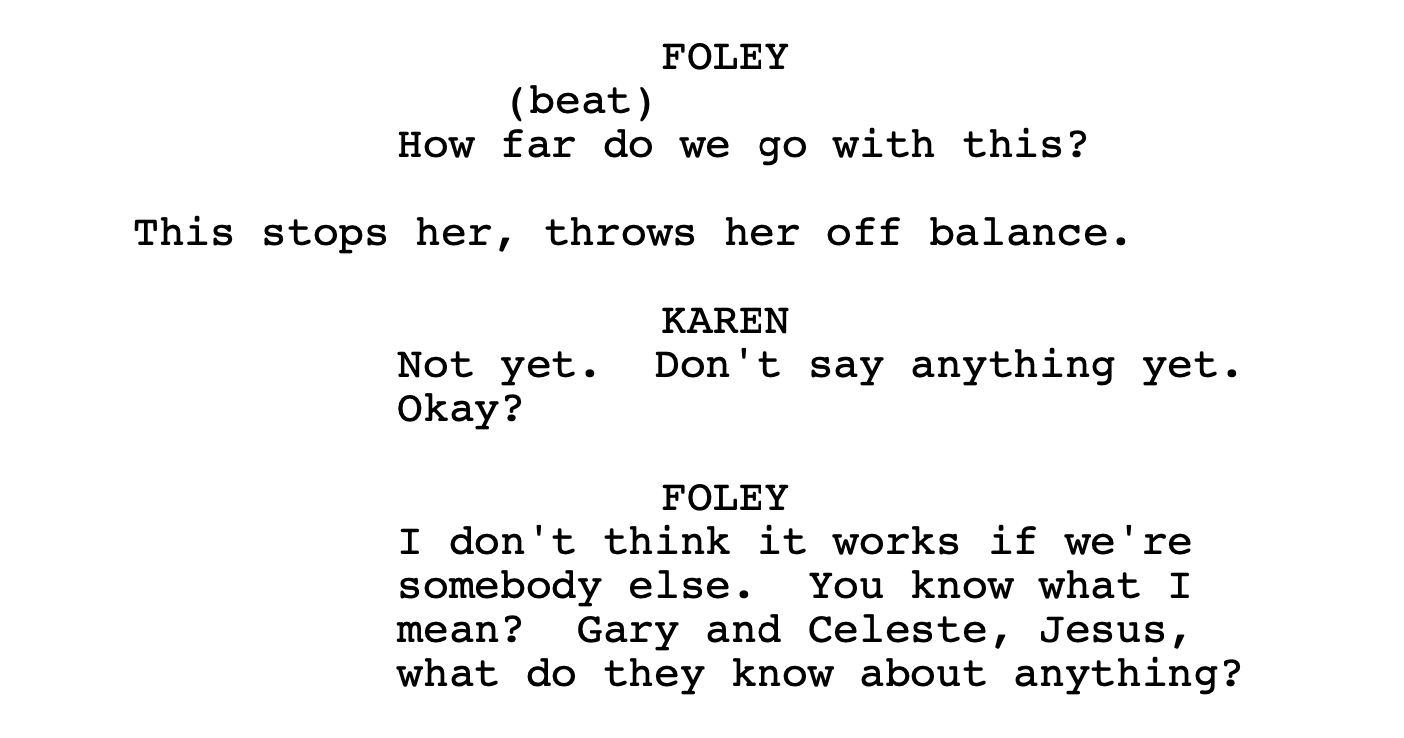

The talk stays small as they cozy into this framing. They delve into the Gary and Celeste of it all, and now we’re A-Camera, B-Camera, C-Camera for a stretch - including a long passage of dialogue in the shared two-shot - with the cuts fewer and further between as the intimacy compounds itself with each passing line.

It’s Jack who breaks the Gary / Celeste runner, which Karen reads as a hard return to real life, but Jack counters is the whole point of what they’re doing - this isn’t about adopted personas or even job titles or how they’ve spent their lives - this is about them.

For this momentary disentanglement, we return to OTS singles, closer and more intimate than the previous angles - each is still in the other’s shot, but we can’t see their faces. The spell is in danger of breaking.

OH, BUT THEN:

As Jack unfolds his theory on what’s going on with them, we move into a handheld CU of him - less escapable, less sure of itself, anchored only by Jack’s certainty. Karen hangs on every word, her framing matching/complementing his.

NOW: here’s where script and movie deviate. In Frank’s rendition, once Karen agrees to Jack’s thesis, Jack makes a move …

… and the scene moves to Karen’s hotel room.

But Soderbergh and Coates take a different approach10, keeping Jack and Karen’s dialogue in the bar, but intercutting shots of them in the hotel room.

As Karen contemplates Jack’s thesis, he sets his hand over hers, and we match cut to the hotel room - change in axis, softer/warmer light - where he lays his hand over hers, this time not on her drink, but on her thigh.

Up to this point, the movie has played with time - dipping into flashbacks, freezing frames on key moments (as below, right) - and in its playfulness, it puts us just off our footing, leaving us to wonder, are we watching the evening play out nonlinearly, or are the hotel room shots a fantasy while they’re still sitting at the bar table?

And if they are fantasy, whose? Is Jack’s hand lingering on Karen’s chin in his imagination, for how he’d like to appreciate her face, or how Karen would like for him to?

The answer is open for interpretation, but to my eye, it’s both. After spending the movie circling each other, they’re together, and I do mean together.

Their dialogue continues as a teasing series of advances and retreats, intercutting attitudes between the hotel bar and the hotel room. Karen brings her drink out from under Foley’s hand (retreat), looks away to take a swig (retreat) and then fixes him with a “your move” look (advance) in a series of hairpin turns in about three seconds of screentime.

The next series of hotel room shots backtrack from the hand-on-thigh business of a moment ago - is it a retreat to a moment of safety before they get ahead of themselves? Is it a rewind to savor more of the building moment?

“Why not both?” ask Soderbergh and Coates.11

Intercut with this, the body language at the bar table steadily loosens up. This is becoming a date.

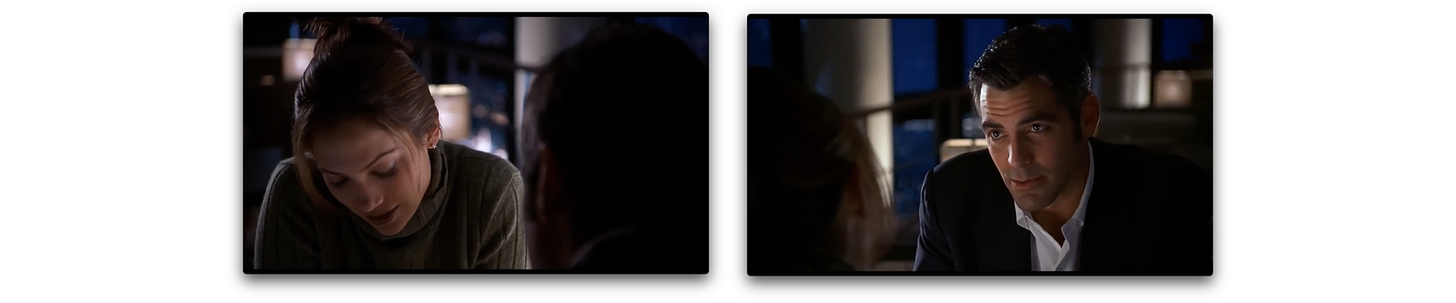

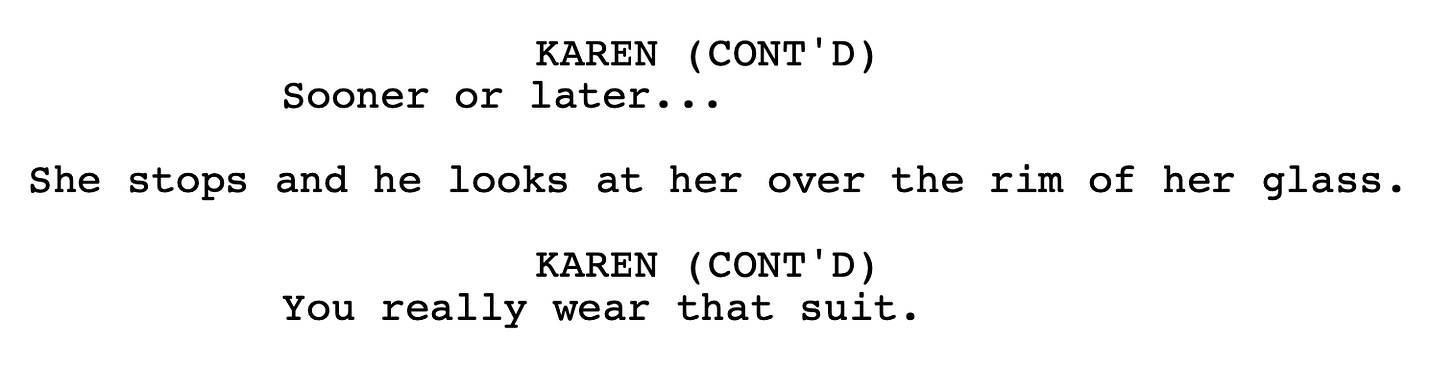

As the hotel room intercuts grow more intimate, it’s Karen who nearly fractures the moment, before catching herself.

And when Foley counters —

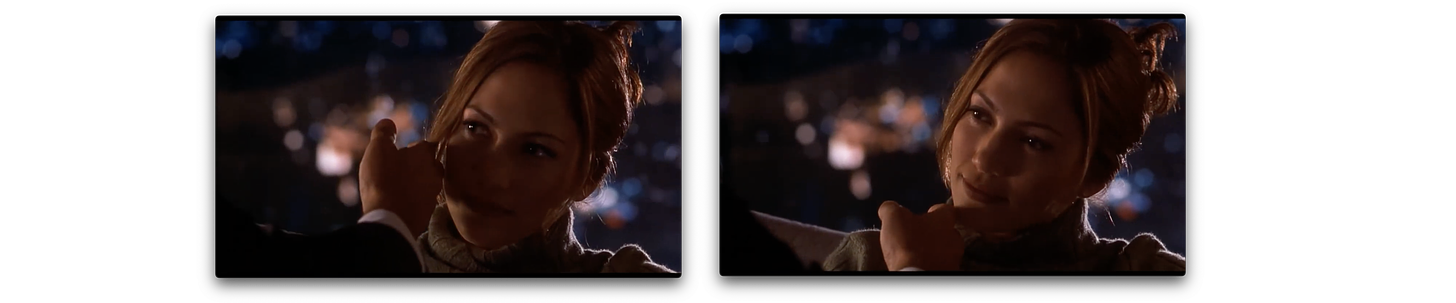

— she changes the subject to the intimacy of their car-trunk meet-cute, and that’s when the moment in the hotel room - delayed as long as possible by a few aching, luxuriant dissolves - is allowed to land.

From here, the dialogue at the table skates dangerously close to talking about Foley’s partners in crime, even as the hotel room action - imaginary or predictive - heats up.

Even action as simple as “move to bedroom, get undressed” gets packed with tonal shifts under Soderbergh and Coates - Foley and Karen’s hesitancy toward really being vulnerable around each other (more hers than his) puts distance between them; but in the intimacy of the staging, this last-line-of-self-defense makes them look for all the world like a long-married couple. They’re not ripping each others’ clothes off, as much as they might like to, but it’s presented without sacrificing any heat.

From there, they treat undressing as a series of escalating dares - “How far do you want to go with this?” Foley asked only minutes ago - a façade that then melts to delight, a kind of acknowledgement of the silliness of the situation, and real excitement to be there.12

Back at the table, it’s Karen who introduces the idea at the heart of the story —

— with Clooney’s line-reading (and Davis’s handheld shake) showing Foley caught flat-footed, hearing his hard-to-deny wish come out of Karen’s mouth.

It’s also Karen who sits back from the bar table two-shot (Davis panning with her - Karen’s not getting out of it this easily), thinks for a moment, then lowers the boom:

These are two of the most significant changes to Scott’s script: originally, the suggestion to move from the bar to the bed was Foley’s —

— which makes sense when the line is the halfway point of the sequence. By then, Foley is still rolling the dice that Karen won’t reject him or worse (maybe?) arrest him, so he’s pressing his luck with the suggestion; Karen, for her part, is letting herself into the situation only gradually and, as scripted, still has a ways to go.

By repositioning it as the punchline of the scene, it stitches Soderbergh and Coates’s parallel stories together, making it track all the more that it would be Karen - the one with real power in the situation anyway - to finally be on board with the “time out” of it all. Foley, for his part, has lost the hesitation of a moment ago, and his poise and the camera are steady as a rock. His “yeah” is less an answer to her question than an affirmation of the situation that they’re both in.

Only then do we get them properly in bed together - backlit and silhouetted, still hidden13. Tellingly, this is the last freeze-frame14 to appear in the movie, a stylized device used throughout that Soderbergh & co. deliberately shed as the story moves out of “movie” into “real.”15

IV. LONG RIDE TO FLORIDA

So really, what makes this my favorite movie of all time? It can’t just be “look at how much I can talk about it,” because have you read my other posts?

All I can say for certain is, when I told Liam (or Ollie Brady when I guested on Glass Onion Minute) that I’d be covering Out of Sight on 5GM, they each had suggestions for worthwhile scenes to dissect.

Frankly, I could go on like this with any scene in the movie, each so loaded with clear, focused intentionality, a mural’s-variety of brushstrokes and colors, and I’m hardly alone - this is one of those shibboleth movies among “those who know,” y’know?

I can’t say exactly why the Loser Noir subgenre speaks to me - something in the shaggy, bruised, if-I-didn’t-laugh-I’d-collapse attitude hooks me every time.

While there have been incredible entries since then - Shane Black’s Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005) and The Nice Guys (2016) are prime, perfect examples; the finale of Better Call Saul (2015-2022) came as close to Frank’s flawless Out of Sight coda as anything since - how could they compete with the final grace-note of a three-and-a-half-formative-years obsession?

I suppose that, as much as anything, is why Out of Sight is my favorite - by the time I saw it in 1998, I felt like I’d been waiting for it forever.

AG.

V. RECOMMENDED MEDIA

The Switch (Elmore Leonard, Bantam Books, 1978)

Ruthless People (Jerry Zucker, dir., Dale Launer, w., Touchstone Pictures, 1986)

Get Shorty (Elmore Leonard, Delacorte, 1990)

Reservoir Dogs (Quentin Tarantino, w./d., Miramax Pictures, 1992)

Rum Punch (Elmore Leonard, Delacorte, 1992)

True Romance (Tony Scott, dir., Quentin Tarantino, w., Warner Bros. / Morgan Creek Entertainment, 1993)

Get Shorty (Barry Sonnenfeld, dir., Scott Frank, w., from Elmore Leonard’s novel, MGM / Jersey Pictures, 1995)

Jackie Brown (Quentin Tarantino, w/d. from Elmore Leonard’s novel Rum Punch, Miramax Pictures / Jersey Pictures, 1997)

Out of Sight (Steven Soderbergh, dir., Scott Frank, w., from Elmore Leonard’s novel, Universal Pictures / Jersey Pictures, 1998)

Ocean’s Eleven (Steven Soderbergh, dir., Ted Griffin, w., Warner Bros. / Village Roadshow, 2001)

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (Shane Black, w/d., Warner Bros. Pictures, 2005)

Life of Crime (Daniel Schecter, w/d. from the Elmore Leonard novel The Switch, Lionsgate / Roadside Attractions, 2013)

Better Caul Saul (Vince Gilligan, creator, AMC Networks, 2015-2022)

The Nice Guys (Shane Black, w/d., Warner Bros. Pictures, 2016)

NOTE: All images are the property of their copyright-holders. No ownership implied.

The Switch - about two hoods kidnapping the wife of a rich man who doesn’t want her back - was also the “inspiration” for the 1986 gem, Ruthless People with Bette Midler as the kidnapped wife and Danny DeVito as the rich husband. Of course, Ruthless People - and, to an extent, The Switch - is based on O. Henry’s The Ransom of Red Chief, too. In an elliptical pop-culture curlicue, The Switch centers on recurring Leonard characters Ordell Robbie and Louis Gara (played in Jackie Brown by Samuel L. Jackson and Robert DeNiro, respectively; in Life of Crime by Yasiin Bey and John Hawkes); in the later Rum Punch, the novel on which Jackie Brown is based, Ordell muses about the movie “based” on his and Louis’s misadventures in The Switch and how it got all the details wrong. Cherry-on-top, the three best Leonard adaptations - Out of Sight, Jackie Brown and Get Shorty - were produced by Jersey Films, in which DeVito is partners with Michael Shamberg and Stacy Sher.

Your mileage of course may vary, but for me, two of the best adaptations besides today’s subject are Manhunter and Silence of the Lambs, where screenwriters Michael Mann and Ted Tally, respectively, realized the strong points of the source material, and worked out new ways to make them cinematic.

The worst examples are Tom Hooper’s Les Misérables and Cats, bank so hard on audiences’ affinity for the totems and touchstones of the source material, they forget to make the case for themselves as movies.

A fourth-wall-warping tip-off that you’re watching an on-the-fly romance akin to Three Days of the Condor.

In a throwaway joke that never fails to get a laugh out of me, earlier we see Jack doggedly calling every single hotel in the phonebook in alphabetical order to see if Karen’s staying there; the punchline is that she’s staying at the Westin.

To both their credit, they give lovely, note-perfect performances, nailing their middle-managers’ “But I’m a nice guy” entitlement.

In one of Soderbergh’s signature meta touches, the third businessman at the bar, never seen in focus, is played by Joe Coyle, Clooney’s lighting stand-in, so that when it is Foley who approaches her, we get a split-second misdirect that it’s the businessman trying to live where his buddies have died.

The Zippo came into the picture when, in a meeting with Soderbergh well before shooting started, Clooney restlessly fidgeted with a Zippo, catching Soderbergh’s eye with its bit of flare and tartly rhythmic sound. My pet theory is that The Isley Brothers’ It’s Your Thing was chosen to open and close the movie not just for how well it fit the movie’s tone and milieu, but for how its guitar hook mimics the click-flick-clack of the Zippo. Frank, for his part, made it an essential part of the movie’s new coda, the only time in the movie that the Zippo is referenced directly, instead of being a visual motif.

In any number of ways, Out of Sight and Ocean’s Eleven are in dialogue with each other, much the same way Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Sting were three decades earlier, but that’s a whole other essay. It’s coming. Most critically, Ocean’s Eleven is not in the Loser Noir subgenre. Like I said, the whole other essay is coming.

Inspired by (or copied from, depending on how charitable you’re feeling) the legendary Julie Christie/Donald Sutherland sex scene in Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973), with more than a dash of the chess game from Norman Jewison’s The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) and the seduction-by-food of Tony Richardson’s Tom Jones (1963).

In a preview of the even chewier time-play Soderbergh and Sarah Flack would get into a year later in The Limey (1999).

I mean, why shouldn’t they? Hesitation may track for the characters, but ultimately, this is Jennifer Lopez and George Clooney in their prime (redacted bc have you seen them lately??) going to bed together, the baseline promise behind every romcom.

“Out of Sight,” if you will

It’s a freeze-frame when you’re watching the movie. Every image I’ve included is technically a freeze-frame, I understand how still images work.

Without sacrificing an ounce of style, btw.