This was written during the 2023 WGA and SAG/AFTRA strikes. The work covered here would not exist without the labor of the writers and actors currently striking for improved working conditions and fair pay.

::

As with my last post, and probably the ones to follow, this one will start with personal history, recollections and observations regarding today’s 5GM selection. If that’s not of interest to you, I recommend skipping to II. Two.

I. You Know (His) Name

In 2005, for the third time in my life, I witnessed the media blitz around the announcement of a new James Bond.

As I recall, the announcement was met with incredible skepticism, which to my interpretation could stem from two possible sources:

We were exhausted being a few years into an unwinnable forever-war with a draft-dodging fake cowboy running things with all the statesmanship of Slim Pickens astride an h-bomb.

The new James Bond had blond hair and blue eyes.

My own ambivalence to the news likely stemmed from the former (though it’s possible most adults met the announcement of a new Bond with ambivalence because real life is happening around them; this being my first go-’round as a grown-up, I assumed I was the first), though I had misgivings of my own, based on my nearly two-decade tenure as a die-hard, tough but fair Bond fan.

As the saying I mentioned in my last post goes, nobody hates Star Wars more than a Star Wars fan, but really that’s a synecdoche for fandom at large - the things we love enough to let into our hearts we also judge most harshly for disappointing us.

That was me when it came to Bonds, having been a passive admirer of them as a kid, then fully becoming an obsessive around the age of 11, after Timothy Dalton’s first (in hindsight, admittedly mid) outing as Bond in The Living Daylights. I spent the sixth grade trying to catch up with as much of the Bond catalogue as I could, while memorizing villains, allies, Bond girls™, theme song performers, etc., like other kids devoured baseball stats.

By the end of middle school, I’d managed to catch all (then) sixteen Bond movies, made a few half-assed stabs at reading Ian Fleming’s (breathtakingly racist and homophobic) novels, and had a particular coming of age experience while watching Licence to Kill the summer I was 12.

(On the For Your Eyes Only episode of the indispensable James Bonding podcast, guest Thomas Lennon theorized with hosts Matt Gourley and Matt Mira the special time in a boy’s life when his focus shifts from the cars and gadgets and action to the Bond Girls™, naming it the Bond Mitzvah; that I was quite literally studying for my bar mitzvah when Licence came out sweetens, cements and ultimately proves Lennon’s theory).

When, in 1994, Pierce Brosnan was announced to succeed Dalton, it brought a sense of gratifying inevitability - Brosnan had famously been in the running for the role until the producers of his tv series Remington Steele actively fucked him over, losing him the role to Dalton.

The years since Licence - then the longest gap between series entries - had seen me through the rest of middle school, all of high school, and into college, enough time to have become about fourteen different people along the way, so it was with all the seasoned wisdom a 19-year-old can muster that I sat down to watch this new incarnation, in Brosnan’s first outing Goldeneye.

Goldeneye has its adherents, and is generally sits high in most series rankings. And while it definitely has a lot going for it, I like Goldeneye, but I don’t love it. Brosnan is charming, sure, but it’s the series that’s on uncertain footing, thanks to the one-two punch of its absence leaving a cultural void filled by Die Hard and its descendants, and of course the (some might say more pivotal) end of the Cold War. Goldeneye misses forty years of east/west hostility so deeply, it spends half its time calling Bond an irrelevant relic, and the other half vilifying Soviet loyalists so that it can still be about east/west hostility.

But as I said, I like Goldeneye, and I like Brosnan … I just think they wrapped some bad Bond movies around him. I know people who adore Tomorrow Never Dies, but it doesn’t click for me. The World Is Not Enough is genuinely boring. And while I enjoy Die Another Day’s lunatic excesses, I can’t call it a good movie exactly.

The sugar-crash of Die Another Day’s extremes - coupled with even more shifting global terrain in the early aughts - led the Bond team (led by longtime series producers Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson) to aggressively reconsider Bond for a new century more transparently and chaotically making shit up as it went.

True to form, Broccoli and Wilson did what Bond movies do best - copy off the other fellow’s paper (I say this affectionately, but being real, this is the series that scrambled which movie was up next to shoehorn Moonraker into the line-up when Star Wars did its Star Wars thing). After Batman Begins breathed new life into another decades-old pop icon by deconstructing him, giving real-world meaning, pathos and purpose to the cartoony totems of his canon, while turning the page on a garish 90s incarnation - and making $373MM worldwide in the process - it would have been foolish for Bond not to do the same.

In addition to drafting off of Batman Begins, Casino Royale also had the unenviable task of sharing an ecosystem with the burgeoning Jason Bourne series, at that point two movies strong, with an esthetic developed by the polar-opposite approaches of directors Doug Liman (2002’s glossy-gritty The Bourne Identity) and Paul Greengrass (2004’s whip-taut The Bourne Supremacy, 2007’s series-best The Bourne Ultimatum, 2016’s let’s-not-talk-about-it Jason Bourne). Where Liman’s Identity worked to dislodge the spy genre from the province of baby boomers, Greengrass’s take combined documentary bluntness with genre-redefining close-quarters combat, favoring clutter and impact, essentially ending action movies’ love affair with Matrixized choreography.

All of this left the Bond series seemingly little ground under its feet from which to remind the world it was still relevant. Fortunately, they found a third avenue to explore; where Batman seeks to whittle Bruce Wayne’s genial charm down to a public show to mask his brutality, and Bourne seeks to shed his lethal skills for a quiet, civilian life, Bond must balance the two - be the monk and the hitman.

The end of a decades-long legal battle finally allowed the rights to Fleming’s first Bond novel, Casino Royale, to revert to Broccoli & Wilson, giving them the framework for their fresh start by going back to a technically untapped beginning. (Casino Royale had been adapted twice before, once as a TV drama with an American Bond; once as a comedy with dozens of Bonds - great soundtrack, pity about the searing unfunniness of it all).

Their intentions for how to reframe the character for the post-9/11 world meant changing Bonds, coming as something of a shock and disappointment to Brosnan (who, after Die Another Day’s $439MM gross, had no reason to expect he wouldn’t be back for another go).

Enter Daniel Craig, via speedboat, looking thin and uncomfortable in his Royal Navy-mandated life vest, and for some reason to the consternation of some people, blue-eyed and blond.

Having seen, but not been all that impressed by, Craig in a few roles (Lara Croft’s second-banana in Tomb Raider, Paul Newman’s sociopath son in Road to Perdition), I decided to continue the personal divestment from Bond I’d been experiencing. After all, if Batman has a ramrod-straight British elder statesman and a spirited gadget guy to play off of, did I really need Bond-brand Bond?

In the interim, I saw Layer Cake (the first time I saw Craig perform with his own accent, and man does that make a difference) and Munich (where a post-Bond-announcement Craig cuts a figure like a Jewish/Afrikaans Steve McQueen, and I started to be like “oh, I get it.”) And while both of these proved to me that Craig was up to the task of playing Bond, I couldn’t shake the concern that, as with his predecessor Brosnan, the creative team wasn’t up to building solid Bond movies around Craig.

The following summer brought the beginning of the marketing campaign, which I met with considerable indifference. Well, no, I’m not sure what the word is, but is there such a thing as active indifference? If there is, that’s what I felt.

(The fact that I was in the middle of a long spell of unemployment and staring down the barrel of turning 30 surely couldn’t have put me in a sour mood, clearly it’s all this new James Bond’s fault).

A new Bond’s first outing is typically sold the same way every time —

Has James Bond Finally Met His Match?

This is Not Your Daddy’s James Bond!

— so when Casino Royale came out of the gate throwing these fists, I was decidedly, proactively ho-hum about it. I’m not sure what other approach they could have taken, but it didn’t shake me from my skepticism about this promised “new” direction.

Let’s jump ahead to November, 2006, where my ho-humness was no match for a new movie to see, even if I was seeking it out for the purpose of being irritated and disappointed by it.

I was fun.

My then-fiancée (soon after, and still, my wife) and I went on a Saturday afternoon to the UA Battery Park (now Regal) - the same theater where a few weeks earlier we’d been blown away by The Departed, and I felt as though I’d already given out my one “This Movie Owns” pass for the season.

I was so fun.

I can’t recall if I had my arms folded across my chest when we sat down, but that was my posture mentally, if not physically.

Lights come down, trailers roll, the movie begins.

The company cards roll up in black-and-white, and already I’m running the who-gives-a-shit live-commentary in my head, “Oh wow, black and white, so daring, what a departure from HOLY SHIT JAMES BOND IS DROWNING A MAN IN A URINAL.”

I got blown through the back of the theater, and have been chasing that high ever since.

They did it. They fucking did it. This was, as promised, Not My Daddy’s James Bond.

This one, I felt, was for me.

II. Two

It’s a bit of an understatement to say there are formal strictures to Bond movies, to the point where saying “it’s a bit of an understatement” is itself a bit of an understatement.

From Dr. No onward, the key beats that open a Bond movie have been:

Gunbarrel

Pre-title Sequence (introduced in From Russia With Love)

Main Titles

There have been variants to each along the way (Die Another Day’s Gunbarrel features a digital bullet flying at the audience; some Pre-Title Sequences have nothing to do with the main plot, others are pivotal; some are brief, The World Is Not Enough and No Time To Die’s Pre-Titles take nearly half an hour each), but these are the expected elements between the UA (or MGM) company card and the start of Bond’s latest adventure.

Casino Royale, to my above-mentioned ho-hum, notably deviates from this by skipping (for now) the Gunbarrel. This feels like a small, who-cares change - a way of achieving the unexpected by doing the exact inverse of what’s expected, and if CR had stayed this course by simply saying no to its predecessors yeses and vice versa, it would have been a waste of everybody’s time.

Fortunately, returning Goldeneye director Martin Campbell and recent Academy Award-winning screenwriter Paul Haggis (working from a script by series mainstays Neal Purvis & Robert Wade) had more in mind, and the result is a meditation on what it means to be a hired killer in any era, but especially in one where any sense of New World Order has fallen to the chaos of extranational action and terror.

(Granted, it has Bond crashing through drywall unscathed, saving himself from a heart attack by poisoning, and getting his balls smashed in by a length of rope, so as meditations go, it’s not exactly Powaqqatsi.)

We begin in black-and-white, in Prague, simultaneously throwing it back to Casino Royale’s origins as a 1954 episode of the action anthology Climax!, and acknowledging the winds of change with a setting perhaps best known for transitioning from embattled Cold War city to thriving travel destination.

When Rifftrax zinged that they’d accidentally thrown on an old episode of The Avengers, it’s only half a joke, since that era of espionage is deliberately invoked by Campbell and co., especially in the stark light and shadow of Phil Méheux’s luminous monochrome cinematography.

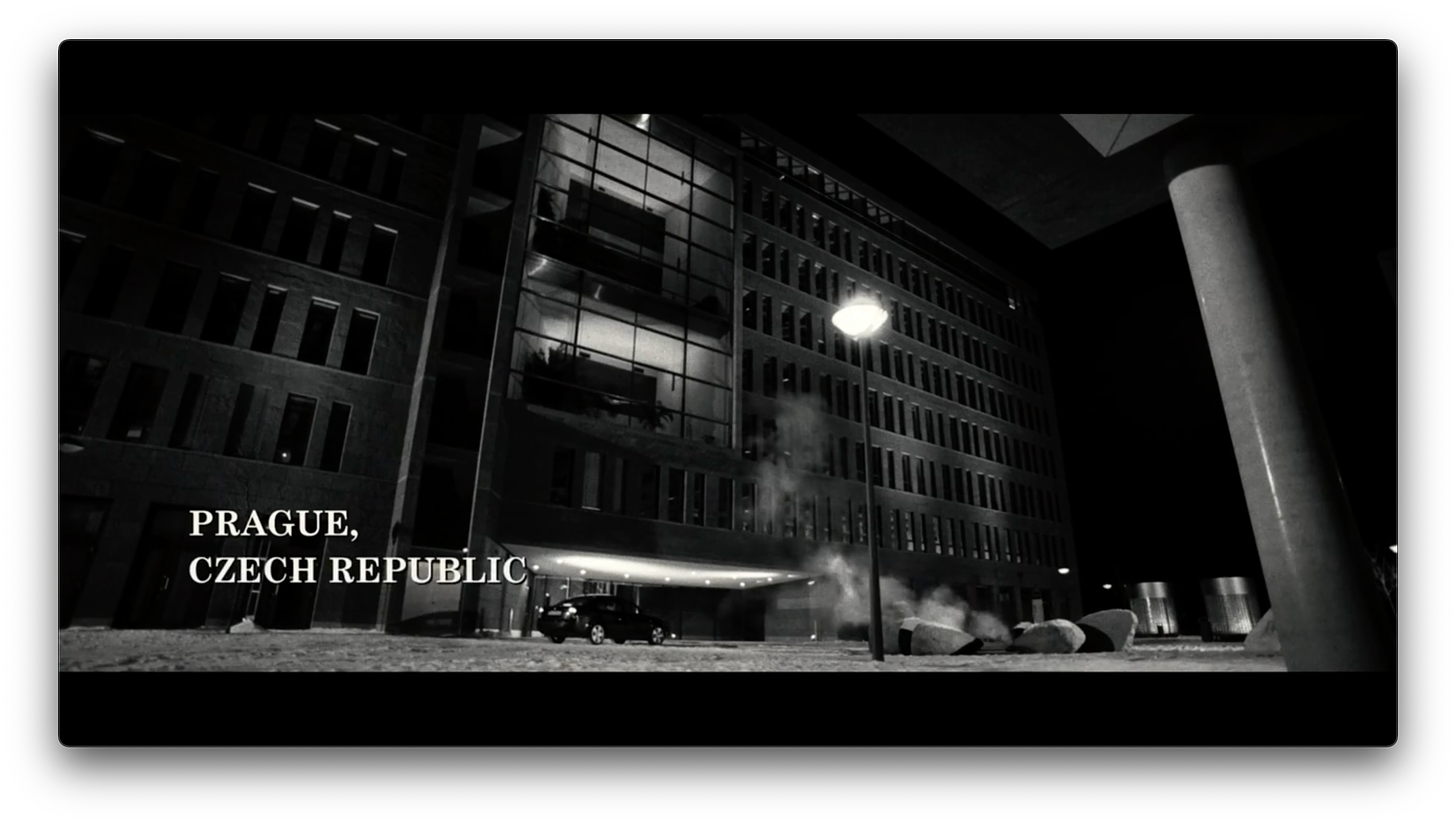

A sedan - gleaming black in this world comprised not insignificantly of blacks, whites and grays - pulls up, and gives us the first face we see: Dryden (Malcolm Sinclair), a corrupt MI6 section chief working out of the British embassy. Sinclair’s Dryden reads immediately as a figure straight out of John LeCarré, cut from the same “classic Whitehall mandarin” cloth as Bond’s eventual Spectre antagonist Max Denbigh (Andrew Scott).

Dryden’s entrance continues the conjuring of Mid-Century paranoia, the low angle distorting Dryden’s features under his period-invoking ushanka (I can’t help but wonder if Sinclair was cast in part for his magnificently photogenic combination of nostrils and expressive brow-furrow).

The composition deliberately pins Dryden on the line between light and shadow, making him a dividing line between the modern and classic architecture styles of the embassy behind him (in actuality Prague’s Danube House, a wedge-shaped office building).

Establishing the low-angle outside, Méheux and Cambpell create a natural transition for (legendary) editor Stuart Baird to seamlessly bring the action inside, as Dryden takes the elevator. Here, the high-contrast black-and-white reduces the modernist architecture to shapes - the circle-and-rectangle base of the elevator, the grid of skylights, the cylindrical glass curve of the elevator car. The shot lasts only seconds, leaving us to absorb shape and motion first, then backfill our understanding of the geometry we’ve just watched as physical elements in a comprehensible space, reminding us however subliminally of the rudiments of how film works in the first place.

Aboard the elevator, we switch perspectives, with a dutched down-angle of Dryden (and friends, the top of Sinclair’s nose is, through Méheux’s lens, just as marvelous as the underside).

A reverse angle gives us Dryden’s POV as he waits for the elevator to complete its journey:

(Viewing the sequence shot by shot for this essay, I was struck by which number the elevator counter cuts off on, giving us a hint about which “number” waits for Dryden.)

Six shots in, CR fulflls its Bond movie mandate as aspirational travelogue with this stunning interior shot (where, again, Méheux’s eye reduces the architecture to coldly beautiful geometry), with Dryden’s solitary figure purposefully on the move. A gentle push-in marks the first moving-camera shot of the movie, as Dryden’s brisk pace easily outstrips the barely-pursuing camera; wherever he’s going, he’s in a hurry to get there ahead of us.

I appreciate that we’re only thirty seconds into the movie, but can we not hold a beat to appreciate how well an intelligently-made movie can convey its intent wordlessly, soundlessly and economically? We don’t know this man’s name, but already we’ve been given clues - his stern expression, the lateness of the hour, the emptiness of the building - that we’ve been trusted to assemble into the notion that this guy and his splendid nose and brow are up to no good.

(Look, I know this is about as profound an observation as “twenty-four still images, shown in rapid succession, simulate movement,” but it’s so easy to forget the building blocks of what make this art form so, well, moving, that it becomes worth reiterating.)

Dryden arrives at his office, his face flashing momentarily white in the ray of hallway light (1), before the camera tracks right and pans left to follow him across the office (2). As it does, it re-centers the frame around the back of a chair in the foreground (the black camera-right mass in (3)).

Dryden’s movement - and the camera’s - stop short in a brief, Spielbergian “reaction first, object second” reveal …

… that, to his arresting surprise, his safe has been opened. Whatever has brought Dryden to the office so late is already out of pocket. He’s not given much time to think about it before a deep voice, originating from that chair, pulls his and the camera’s attention:

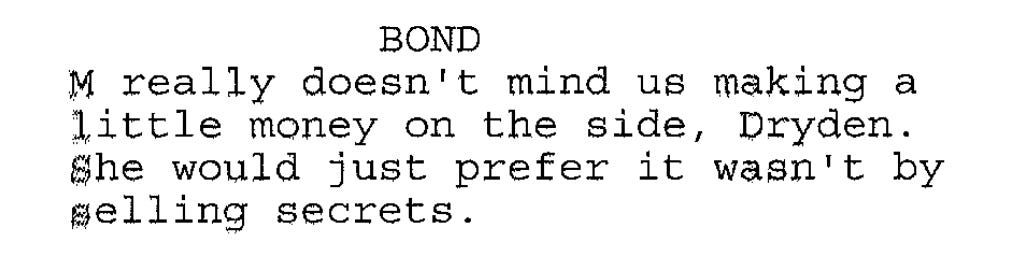

Of note: in the movie, Bond says “M doesn’t mind you making a little money on the side.” As scripted, Bond’s line invokes the MI6 old boys network; as delivered, it’s a judgment.

Also of note: continually proving to be one of our more versatile working actors, Craig’s subtle voice work is remarkable. While he can work hambone-broad miracles with it (Logan Lucky, the Benoit Blanc mysteries), his usual timbre is high, centered in his sinuses. For Bond, he brings his voice into a lower register, into his chest.

We cut to a medium shot for the “selling secrets” punchline:

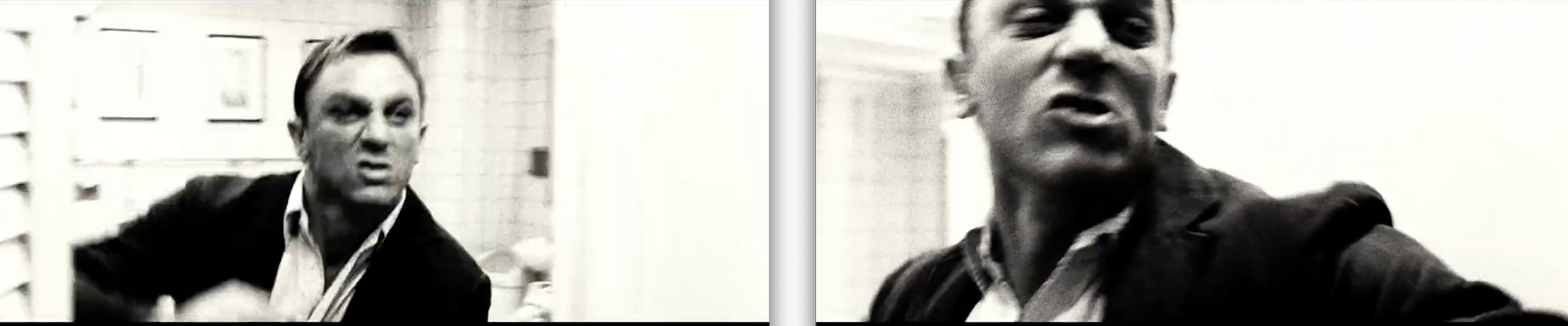

Our first look at the new Bond, and two impressions arise immediately:

This is not the green, long-haired Daniel Craig in the life-vest on the Thames

For Bond die-hards, the framing, the staging, and the icy physicality with which we meet our new Bond conjure nothing so much as a classic Bond antagonist:

And since, as I’ve mentioned, everything in CR to this point has relied on our skills of comprehension to piece together, this can’t possibly be accidental. The filmmakers have taken the general apprehension over a new Bond - especially this new Bond - and weaponized it; we’re not meant to be comfortable with this Bond. As with his license to kill, his Aston-Martin, and all his other totems, our trust is another thing this Bond will have to earn.

Dryden, his secrets brought literally to light (1), settles into his desk chair, a posture of negotiation to Bond’s eye (2), but to ours, a coiling offensive posture.

Dryden seems to relax:

His posture slackens from (1) to (2), and he plucks off his gloves (turning black hands white, a diversionary show of confession), as he appears for all the world (and, he’s hoping, to Bond) to settle in for a chat.

He pontificates about the relative security of his position - claiming not to be frightened by Bond’s “theatrics” (letting us know it isn’t just Campbell, Méheux and Baird playing up the drama here, but that Bond has made a conscious choice to stage the scene), or even by Bond’s presence here, since a Double-0 would have been dispatched if M was certain of Dryden’s corruption, and Bond doesn’t qualify.

We return to the master - Bond in shadow, Dryden in light - as Dryden continues to brag about his access and oversight to Bond.

Baird returns us to Dryden’s single - his place of power, large in the frame with eyeline directed down at Bond - to deliver a surprising bit of information: to Dryden’s considerable knowledge, Bond hasn’t killed anybody. Achieving Double-0 status, we learn for the first time in the series’ forty-four year history, requires two kills.

A hard cut to Bond’s single as he finishes Dryden’s sentence is a study in contradictions - in contrast with Dryden’s framing, Bond is small in the frame, eyeline aimed upward at Dryden, yet Bond is calm and abrupt as he interrupts the “larger” man.

We don’t have much time to think about it as an even harder cut takes us to —

— well, we don’t yet quite know where we’ve been taken, only that it’s somewhere else. Bright where Dryden’s office is all shadow, kinetic where Dryden’s office is still, tight where the framing in Dryden’s office is wide to the point of dwarfing its occupants.

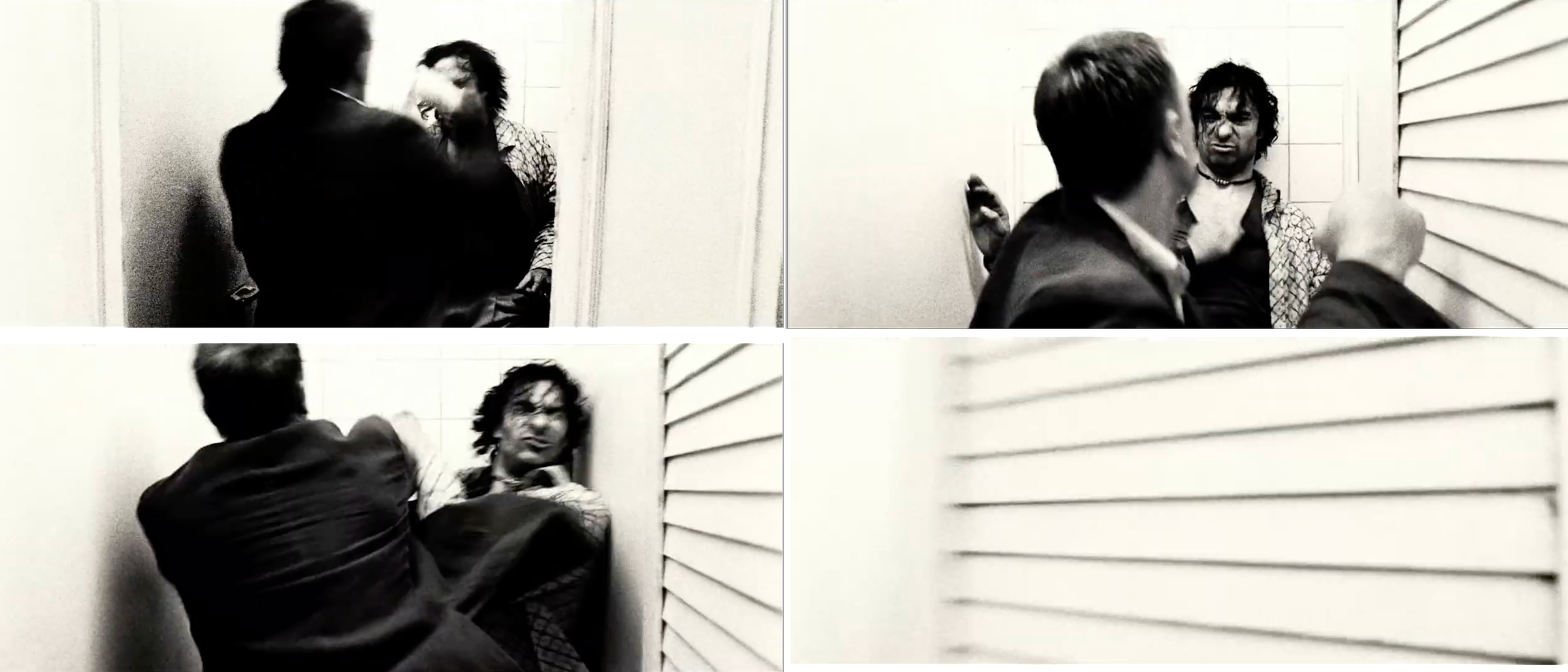

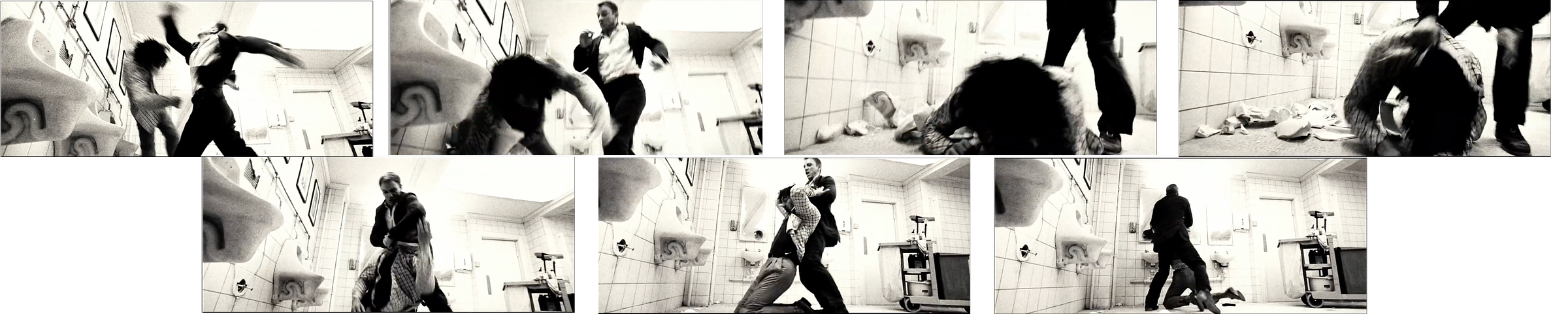

Here we see the Greengrass influence, as the fight begins in medias res, stripped to visual abstraction, as Bond fights Fisher (Daud Shah) in the cramped quarters of a public bathroom.

(Originally, this sequence had a more conventional lead-in, showing that Bond is in Pakistan, tailing Fisher from a cricket match - you can watch the extended version here - but in the final telling of the scene, this isn’t needed. Your mileage may vary, but to my eye, the context adds little and subtracts tons.)

The perspective widens to show us that, with that disembodied kick, Bond has sent Fisher through the door into a toilet stall.

(Note: on frame-by-frame rewatch, I found that that’s clearly a digital replacement, putting Daniel Craig’s face onto the body of his stunt double, Ben Cooke; I can’t tell what about this particular shot made it double-worthy, considering how much of the sequence is handled by Craig, but this is as good an opportunity as any to shout out Ben Cooke’s work as Craig’s double on this, and in Quantum of Solace and Skyfall.)

(And while we’re on that subject, how about a hand for stunt coordinator Gary Powell and second unit director Alexander Witt who shot, pardon the expression, the living shit out of this men’s room.)

Craig’s parallel performances - here and in Dryden’s office - make for their own study in contrasts, his face impassive in the office, a thick-featured mask in the bathroom as he relentlessly attacks Fisher.

Here, we see that tightrope duality in action - in Dryden’s office, Bond plays the monk; in the bathroom, the hitman. What M wants - and what he has to learn - is how to be both at once.

Reverse Angle: Bond throws a right cross at Fisher’s face (1); then, as the camera reframes tighter and to the left (2), he throws another that misses, spinning him into the stall with Fisher (3), and slamming the door in our face (4).

Here, a sequence that until now has largely played on our expectations, now plays against them - the door closing feels like the end of this story beat, as though we’re about to cut back to Dryden’s office … but this isn’t that movie. The true ugliness of what Bond does - which, let’s be clear, is committing government-sanctioned murder - doesn’t get to hide behind closed doors here.

Nor can the ugliness be contained, as Bond turns being pinned to the stall wall (1) to his advantage, shoving Fisher backward through the next two adjoining stalls (2-3), against the opposite tile wall (4).

This Bond may be learning on the job how to kill, but I guess the covert part of his job will come later.

Judging by the change in hair-length and assiduous avoidance of letting the camera see his face (1, 3, mostly 4), that’s Ben Cooke taking the dive out of the stall onto the floor, with the insert of Craig (2) to sell it. It makes me assume that any shot where we can’t see Craig’s face is probably Ben Cooke.

(A general, though hardly universal, rule is if you can’t see the actor’s face during a stunt, it’s the stunt double. I don’t mean this as a GOTCHA!, btw - a thing about me is I never get mad at a movie for a Texas Switch or visible stunt double - it took me nearly 20 years watching this sequence even to come close to catching it, and frankly, details like this help me reverse-engineer the decision-making behind the movie; for me, the seams make the garment.)

Bond gets to his feet first, which is pivotal to the rest of the sequence - from here he’s able to increasingly dominate Fisher:

A kick (1), a shove (2), a block when Fisher tries to counter (3), and BAM —

— taking advantage of Bond’s reverie, and our engrossment in the bathroom fight (1), Dryden pulls his foreshadowed gun (2).

It’s a beautiful pair of edits from Baird:

Ending the scene with Fisher swinging the trash can feels abrupt, but the cut comes right on the action of Bond kicking the trash can away, which keeps the editorial rhythm of the scene, even while ending seemingly prematurely

We return to Dryden in a close-up, but then cut wide as he brings the gun to bear on Bond, which adds impact to the action.

Bond, for his part, seems unflappable, and the out-of-focus foreground glint (maybe on the arm of one of Dryden’s unoccupied guest chairs?) heightens the sense of his relaxation by suggesting the form of Bond having his feet up.

Dryden tries for it, but the gun’s empty (1). More good nostril acting from Sinclair selling the “Oh shit” pivot (2) as Dryden realizes who’s got the power here (3).

Playing off Dryden’s “We barely got to know each other,” Bond responds “I know where you keep your gun,” then dryly adds “I suppose that’s something.” It’s the first real rejoinder of Craig’s career as Bond, and it’s not hard to conjure the breezy confidence of how Connery or Moore or Brosnan might have delivered it. Craig’s under-delivery - icily humorless except for the almost sarcastic trill he puts on “gun” - communicates how Craig’s performance won’t be what we’ve come to expect.

Back to Dryden’s single, where the top half of his face hasn’t changed a bit, but the slackening of his jaw and the deepening of his worry lines tell us that this isn’t the same Dryden from before he pulled the trigger.

“How did he die?” he asks, giving the audience the perfect cue to ramp our focus back to the bathroom fight, but that isn’t really what he’s asking; now that he knows that Bond’s a killer, he’s asking how Bond plans to kill him.

“Your contact?” Bond asks. We’re seeing the methodical nature of how Bond thinks - he’s so focused on the target in front of him, he has to consciously decompartmentalize to return his thoughts to the only man he’s killed so far.

(Of course, that’s one interpretation - another might be that the flashbacks are strictly nondiegetic, meant for our entertainment and enlightenment, and that Bond absolutely hasn’t lent a thought to Fisher since killing him.)

Worsening matters for Dryden, whose imagination of his coming death must be running riot by now, Bond only answers “Not well.”

(The economy-as-wit in the dialogue of this sequence is remarkable, and a massive part of why, out of sixty-one years and 25 movies, this is the scene I chose to cover).

On that, we SMASH back to —

— Bond, still with the upper hand.

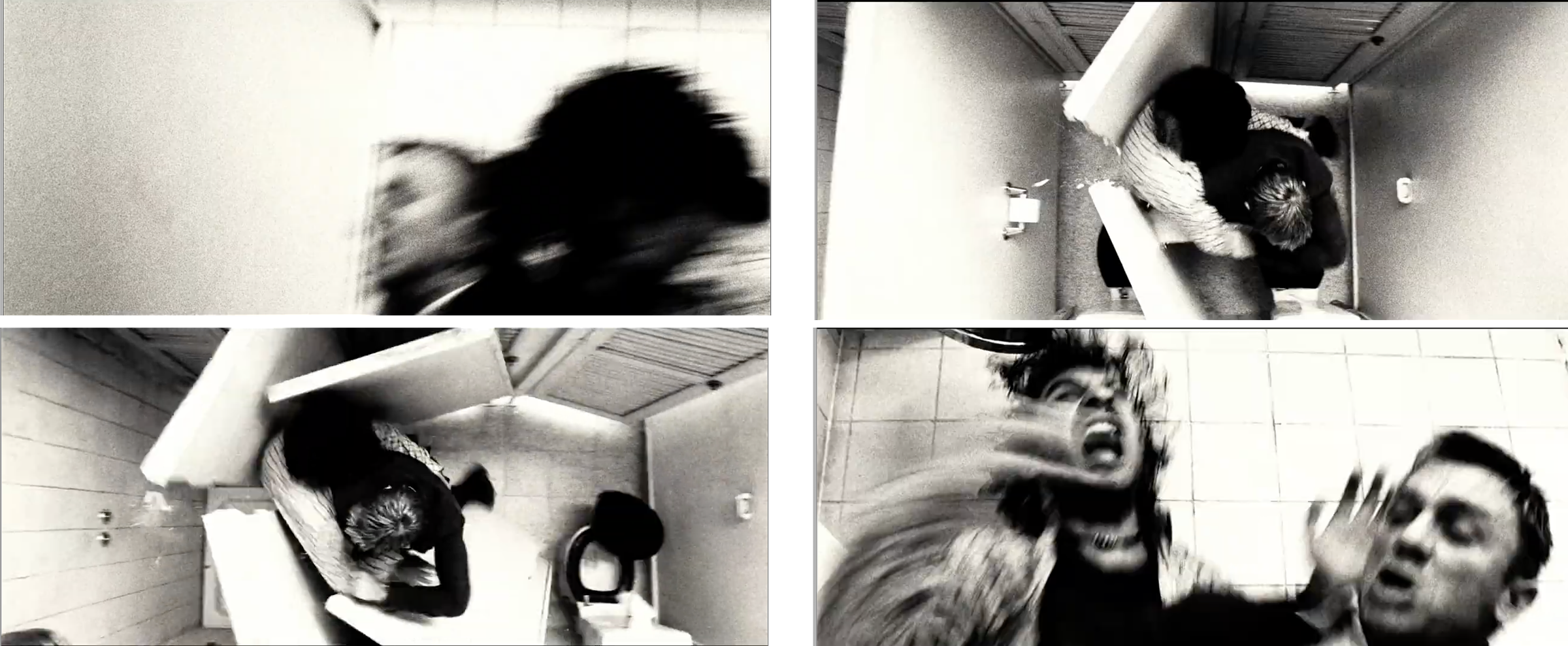

The seven frames above are all from one continuous shot, and while it may not make anybody forget the Copa shot in GoodFellas, it highlights something that’s been lost in the ensuing years’ reorientation of shooting movies to benefit a post-production workflow: successive actions captured in one shot, rather than broken into several. It’s a subtle thing, but it’s far thinner on the ground now than it was twenty years ago, and I miss it.

Here, Bond uppercuts Fisher (1), knocking him through a urinal (2) on the way to the floor (3), and while this would seem a logical cut point, the shot continues, with Bond hoisting Fisher to his knees (4-5), and grabbing the collar of Fisher’s own shirt to choke him with (6), before dragging him over to the sinks (7).

The inclusion of all of these actions in one shot gives us another example of the tension of the paradox:

Throughout, Bond is in control of Fisher, BUT

The process is laborious, messy and time-consuming - hardly the work of the Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang we’ve come to rely on.

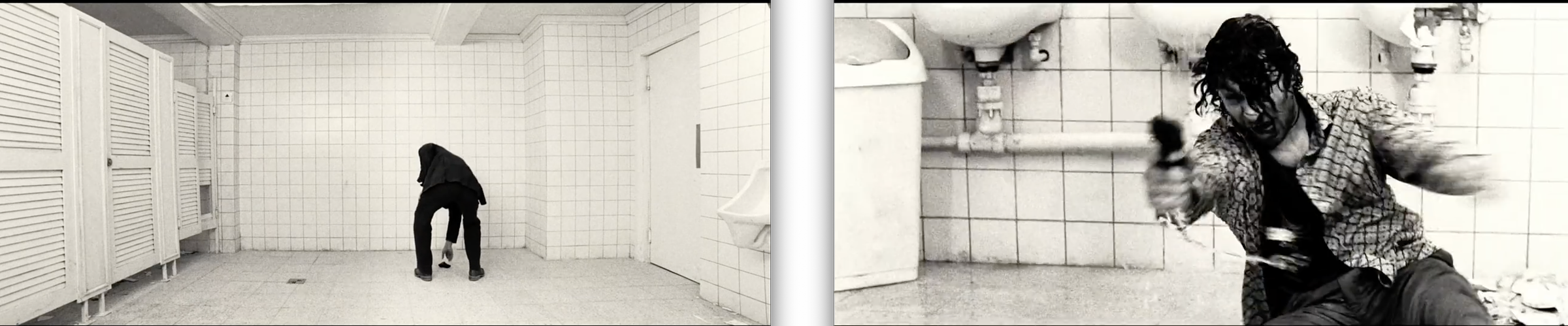

From here, Campbell, Witt & Co. could just as easily have jumped to Bond drowning Fisher in the sink (I know I said “urinal” in the introduction, but that was the first impression the movie left me with all those years ago, what with all the shattered ceramic and slippery tile of these three minutes), but they seem intent on establishing for us that there’s shoe-leather in the act of murder, and they don’t spare the agony along the way —

— even taking time to contrast Fisher’s suffering (1) with Bond’s brutal concentration (2). Here we see the hitman struggling to be the monk because what comes next is the hardest part.

Bond moves Fisher in for the kill - an unceremonious drowning in a men’s room sink. It’s another carefully calculated move on the filmmakers’ part, setting this seminal moment in Bond’s life in squalor, a stark contrast to the series’ accustomed glamour.

Sure, this Bond will go on to take men’s lives in high-drama settings like the Bolivian desert, in the chapels of burning estates, in the caldera of a mad poisoner’s garden. But held against those moments - and prior Bonds’ similar coups de grâce - this Bond begins his dubious career much closer to the gutter than the stars.

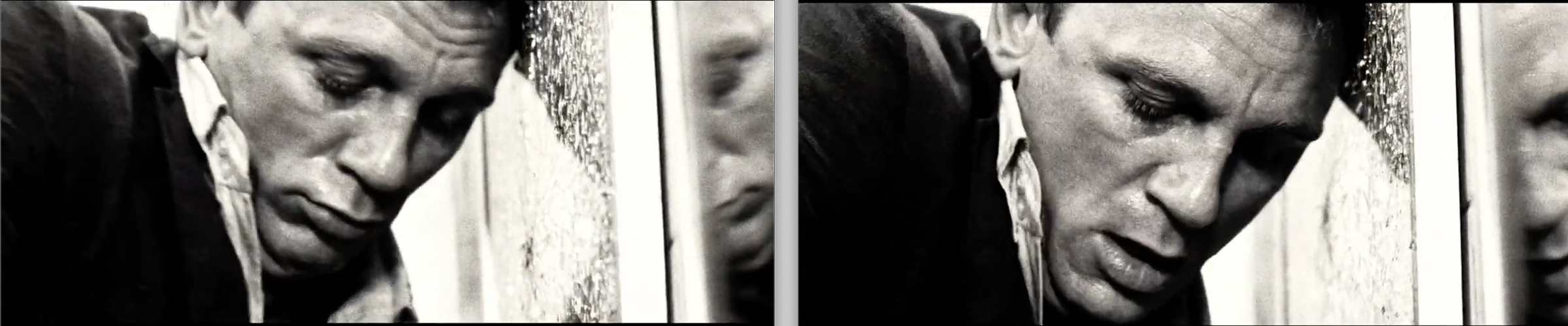

Harder still for Bond in this moment, we introduce a new element which will recur through the movie - the mirror. Later, our first look at Bond in his signature tuxedo comes while he clocks himself in the mirror, admiring how well he looks the part; after a particularly vicious stairwell brawl leaves him shaken and his tux shredded, he administers first-aid while downing four fingers of whiskey, glaring at himself until he can regain his calm.

Here, his concentration locked on finishing Fisher off creates a potent image - Bond literally can’t look at himself in the mirror for what he’s doing.

A quick insert shot as Fisher scoops up a discarded gun (1); Bond adjusts his stance to deal with Fisher’s gun-hand (2); a stray round takes out the next sink over (3). In Méheux’s black-and-white, the repeated shattering of porcelain draws a more visceral effect than it might have had in color.

Bond disarms Fisher by bashing his gun-hand into the mirror (1), shattering it (2), and a case could be made he’s killing two birds with one stone - taking Fisher’s gun out of the equation, and removing his own reflection (his harshest critic) from it, too.

Back to the business at hand: Bond moves from a blur (1) to a statue (2), performer and camera unifying and interlocking, steadying for the hard work part.

Bond starts to close the book on Fisher (1), and the perspective provided by frame-by-framing this is that Craig never wears the same expression twice (2, 3). This entire process is visibly as emotional a struggle for him as the exertion of beating and drowning a man to death.

Bond leans in to exert the final bit of pressure needed to close the deal (1), and while he’s right up against the mirror he can’t / won’t look into, we’re given a clear perspective of his reflection in the next mirror over (2). Bond may try to hide his ugliness from himself, but he’s still exposed for all to see.

Fisher goes limp (1). Bond lets him drop (2). And while there’s an air of finality to it, Fisher is still clearly moving.

Again, we see the interplay of performer and camera - a wild reframing at the top of the shot catches Bond at his most ragged. But as the camera locks into position, Bond steadies his breathing, getting past what he’s just had to do, but more critically, squaring himself for what comes next.

Hard part’s over, now comes the hard part.

Back to Dryden’s office for more good face-action from Sinclair, now threading care into his eyes, his brow a few degrees unlocked from the last time we saw him (1).

In a last ditch effort to get under Bond’s skin, maybe play for an extra second or two, Dryden empathizes with Bond’s agony over his first murder. Or, perhaps he knows it’s over, and there’s nothing left to do but connect to another human, even if it’s the last you’ll ever see.

Bond, for his part, is back to impassivity (2), a contrast both to Dryden’s few degrees of warmth and his own facial contortions over Fisher’s tapped-out almost-corpse.

But there’s a subtle change as we look at Bond - now that we know a bit more about this blank assassin, is that a glint of residual pain in his eye?

(There’s literally no difference in his expression here and the last time we were in Dryden’s office, but our experience with Bond can quite literally change how we see him. The Kuleshov Effect is a hell of a drug.)

Frowning by degrees, Dryden resigns himself to his fate, and elects to go out comforting his own assassin (1). "The second is —”

He was likely about to say “easier,” but instead, we widen out on Bond (2) - both to accommodate the massive, silenced pistol he’s produced from out of our blind spot, and to give ourselves a healthier distance from this murderer - as he cuts Dryden off with a bullet, escorting him and his delightful nostrils out of the movie.

Dryden takes the bullet, and we get a flash cut to something it took me endless pause / rewind / slow-advances to catch:

As he falls, Dryden’s hand swipes a photo of his family off the desk. It plays out this fast:

James Bond has just murdered a man with a family. And while we’ve likely seen him do this hundreds of times before, it’s never been pointed out quite like this.

I’ll level with you, this fraction-of-a-second insert is one of my favorite shots in all 60+ years of Bond movies. Not for the shot itself, easily enough mistaken for a whip-pan to kick up the dynamism, but for the care and thought it shows to include such a detail.

Take it out, the scene probably stays more or less the same. But it changes things - the visual rhythm, the impact of Dryden’s death, our feelings about this new Bond with whom we’ve yet to, well, bond - and not insignificantly.

We barely see it. But it’s there. Campbell, Baird, Méheux, et. al., have made us feel it.

(Again that’s clearly a stunt double for Sinclair taking the bullet and the fall, but also again, I don’t care, I love that shit.)

Bond, looking for all the world like his pulse hasn’t so much as blipped (1), stashes his pistol (2), and responds to Dryden’s unfinished sentence (3).

That’s all the eulogy we get for Dryden, as we return one last time to the men’s room:

Bond, well and truly ready to wrap up The Fisher Affair (1), bends to pick up his own pistol, turning his back on Fisher; Fisher, for his part, springs up, gun in hand, ready to flip the script (2), but —

— for the first time, we get a practical gunbarrel open (well, it’s visibly CG, so not practical practical, so let’s say diegetic) - that’s Fisher’s gunbarrel, and that’s Fisher’s blood.

And now, the true reason for the stark white tile of the bathroom setting comes into relief; a case could be made that the whole scene was reverse-engineered to deliver us right to this new riff on an iconic shot.

And all of that - blood, sweat, two lives, not to mention countless toilets and sinks - has all been just to get Bond to the starting line. Nestled into the opening titles is the affirmation that Bond’s cold-open exploits have earned him exactly what he was playing for —

It’s an economical bit of business, stashing the punctuation of the story so far in the graphic open - it not only makes the main titles narratively load-bearing, it lets the focus of the cold open stay on action and emotion. It also ticks the box on something of a foregone conclusion - we knew this new Bond would become a Double-0 so why burn actual story time on it?

I could spend a whole separate essay discussing the Mad Men-prefiguring main titles, but there are better-executed Bond titles to discuss (no shade, this one just feels a little previz/proof-of-concept, particularly when held against the richer work of Craig’s later title sequences), and really, there’s only one essential moment in the sequence:

Our first look at Daniel Craig, the blond Bond, in living color.

As if in rebuke to those who’d rejected Craig out-of-hand for not having the tall-dark-handsome mystique inherent to that point in every Bond, the entire shot pulling Craig out of silhouette is paletted and color-timed to complement Craig’s baby blues, even making them the last part of him to return to shadow.

III. Lesson Learned

The third act finds Bond - having withstood machetes, poison, torture, and a deathless Texas Hold-’Em sequence - settling into a new mode: early retirement.

Lying in the sand, Bond contemplates walking - or sailing - away from MI-6 with his new love Her Majesty’s Government accountant Vesper Lynd (Eva Green). He reflects on the betrayal (he believes) at the hands of fellow agent René Mathis (Giancarlo Giannini), whom he’s fed to MI-6’s rendition teams as a traitor, shrugging it off:

This is table stakes for the dirty business Bond is ready to step out of after one mission, not yet realizing his mistake, and that a far worse betrayal waits.

Ultimately, Bond can’t self-assess his own education (see above re: arrogance and self-awareness), and on the other side of his true awakening, he receives M’s benediction on the matter:

Every death at his hands along the way has gotten easier (except for The Big One, though a death he fails to prevent, rather than cause), and now, he arrives at the culmination of the path that began in a cricket pitch toilet and an office in Prague.

The execution of the gunbarrel gag is telling - beyond the craftsmanship it takes to construct a sequence to build to so perfect a punchline, it’s not simply there for Campbell & Haggis to flex their cleverness - it tells us from the start that, for this Bond, nothing, not even the basic package handed to every Bond, is given; everything must be earned or taken, and everything costs something.

AG.

Note: All images property of their original rights-holders; no ownership implied.